With the advent of the British on the Indian scene, a number of changes

took place in our social milieu and economic set-up. Our traditional way

of life, socio-economic-cultural set-up and values received a rude jolt.

The situation in the field of art was no less dismal. The days of traditional

schools were over. The art schools set up by the British government imparted

instruction that was neither related to our past nor to contemporary European

art that burgeoned with the spirit of new experiments; the emphasis was

solely on outdated academics. Painters not only of Punjab but all over

India were wallowing in a state of utter hopelessness for lack of direction

and guidance. There were two dominant schools of painting in India at

that time. The Bengal school whose adherents were turning out maudlin

imitations of ancient Indian styles, aiming at a kind of romantic revival

of India's glorious artistic heritage and the Bombay School of Art mainly

engaged in poor imitations of western academic painting. The painters

of both these schools could hardly play the role of torchbearers. At such

a critical period of transition, a powerful personality was needed to

show the light to painters groping in the dark. Art forms were clamouring

for a powerful expression. This void was filled not by a man but a woman

painter of Punjab. Amrita Shergil who, soon after her arrival on the art

scene, took not only Punjab but also the entire country by storm.

Amrita Shergil was not a product of Indian or Punjabi socio-cultural

milieu. She was the daughter of Sardar Umrao Singh Shergil and Antoinette,

a Hungarian lady endowed with considerable artistic talent. She was born

in Budapest in 1913, and spent the formative years of her life in Europe.

She dabbled in paint from her early childhood. Her intelligent mother

detected the talent latent in her, and encouraged her to paint. She took

her to Italy and Paris, the hotbeds of artistic activity and the birthplace

of many a historic art movement in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Amrita had the good fortune of studying at the best art school at Paris,

the Ecole des Beaux Arts, under the competent guidance of great masters.

Besides, living in Paris, she had the added advantage of visiting art

galleries, museums, salons, etc. She studied the works of contemporary

and ancient master painters in the original.

Amrita's work done during her stay in Europe till 1934 was largely academic,

consisting of still-life, nude studies, portraits and the like. Her genius

was to flower only after her return to her fatherland, India. She came

here not as a foreigner attracted by the 'picturesque' India, and the

exotic sights and smells; she came here as an Indian in feeling and spirit

and with a mind to make this land her home. Despite her training in western

art, she had complete awareness of and deep respect for India's artistic

traditions. When she set foot on Indian soil for the first time in November

1934, she was haunted by the faces of the unhappy and dejected, poor and

starving Indians whom she saw first around Simla, then in the South and

finally in Punjab, where she was to spend the last days of her life (She

died in Lahore in 1942). After settling down in Simla in early 1935, she

took an important decision of interpreting "the life of Indians,

particularly the poor, pictorially." This, she said, she would do

"with a new technique, my own technique" and "this technique

though not technically Indian, in the traditional sense of the word, will

yet be fundamentally Indian in spirit." These words suggest that

she had a clear idea of what she was to accomplish in the near future.

Amrita guided her contemporary painters not only by her works but also through lectures and articles in which she urged them not to cling to "traditions that were once vital, sincere and splendid and which are now merely empty formulae", nor to imitate fifth rate western art slavishly. She also told them to "break away from both and produce something vital, connected with the soil, something essentially Indian."

Amrita Shergil and her paintings created quite a stir in the field of art not only in Punjab but all over India. Many men painters came under her influence, but not a single woman painter emerged on the art scene of Punjab until the '5Os. This shows that an individual genius, with however towering a personality, cannot change society. The social set-up in Punjab remained more or less unchanged and the middle classes continued to remain culturally impoverished, due to lack of aesthetic awareness. No one, not even painters encouraged their daughters or sisters to take to painting. It needed a great deal of courage and a spirit of defiance against social norms -for women to come out of their cloistered existence and play a vital role in the field of art. This was true not only of painting or sculpture, but also of practically all forms of art - music, dance and drama. In the post-independence era, some liberal families, mainly from the affluent or upper middle class strata of society, started sending their daughters to schools.

Amrita Sher-Gil --Life and Work

by Vivan Sundaram

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Destiny is often made from strange causalities. Amrita Sher-Gil was born of a Hungarian lady who came to India with the socialite Princess Bamba, the cultured and eccentric granddaughter of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Princess Bamba loved music, met the young Hungarian lady Marie Antoinette in Europe, and persuaded her to come on a trip to Punjab. They arrived some time in 1911, and in Simla the Princess and her companion met Sardar Umrao Singh Sher-Gil of Majitha. The handsome aristocratic Sardar fell in love with the charming Marie Antoinette and they decided to get married.

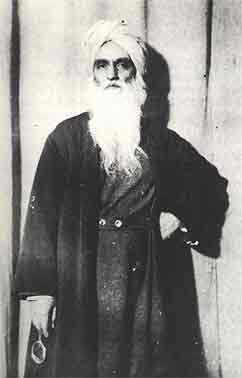

Umrao Singh Shergil

Marie Antoinette

Umrao Singh Sher-Gil came from a well-known feudal family near Amritsar. His father was a warrior of renown who, having initially fought with the Sikhs against the British, had later changed sides. For this betrayal the British gave him the title of Raja and amply rewarded him with estates in Punjab and the United Provinces. Umrao Singh developed very differently from both his father and brother. The latter had transformed his inherited wealth into capital by building up one of the largest sugar factories in India.

Umrao Singh, however, spent his long life in the pursuit of knowledge and spiritual upliftment. A scholar in Sanskrit and Persian, he studied philosophy and religion, dabbled in astronomy, photography and carpentry, and spoke five different languages fluently. Throughout his life he retained the pride of his ancestors, which sometimes expressed itself in sudden anger and impatience. A certain rigidity about the reputation of his family made him feel apprehensive, that the return of his Bohemian daughter Amrita from Paris might disgrace him. He wrote to her saying that since she was not very interested in India and knew nothing of its philosophy or art, she should remain in Europe where she seemed to belong. Amrita replied in September 1934 that she 'was rather sad to realise that you place the conservation of your good name above your affection for us'.

Soon after their marriage Umrao Singh and his wife went to Budapest, where

Marie Antoinette's father, Gottesman was a government official. The Gottesman

family was

culturally sophisticated, thus Marie Antoinette, her sister and her brother

were sought after even in Budapest's upper class soirees. Marie Antoinette

was in many ways the opposite of her husband. She had a gregarious, gushing

personality, which could charm society snobs, but for those close to her could

become unbearable. Her chaotic and hectic life style was the consequence of

her highly nervous and impressionable tempera-ment. Her fits of depression

and threats of suicide deeply affected the whole family and in particular

Amrita, who was especially disturbed by them.

EARLY CHILDHOOD-HUNGARY 1913 to 1921

Amrita Sher-Gil was born in Budapest on Friday 30th January 1913, and in March 1914

Amrita's sister, Indira was born.

Amrita

with Indira (sister) 1922

Amrita

with Indira (sister) 1922

As the First World War had broken out, it became impossible for the Sher-Gil

family to return to India. Fearing that should their children be killed, they

would not receive proper burial, Marie Antoinette had them christened in a

Roman Catholic Church. Although she herself was a Catholic (with some Jewish

blood about which she was very discreet) she was not particularly religious

and did not insist on the- children going to Church.

After the war, the Sher-Gil's attempts to return to India were again delayed.

In March 1919 the Communists overthrew the monarchy and set up a revolutionary

government, which lasted for six months. This was smashed by Admiral Horthy

whose Fascist tendencies unleashed a reign of White terror. The uprising frightened

the Sher-Gils, so they fled to Marie Antoinette's family house situated a

short distance away from Budapest. Although quiet and peaceful, life there

was difficult as the Sher-Gils had little money and food was rationed.

From the age of five Amrita started drawing and painting in watercolours. Her mother would tell the children Hungarian fairy tales, which Amrita would illustrate. The Hungarian country side, its feudal castles, the peasants in their big coats embroidered with bright colours and their houses decorated with bold bright designs made a strong visual impression on her. The first eight years of Amrita's life spent in Hungary were joyful and carefree. She was not sent to a school and a private tutor taught her to read and write Hungarian, which was the only language she then knew.

Amrita

the PAINTER

Amrita

the PAINTER

IN INDIA - 1921 to 1929

Amrita between eight and sixteen years of age

Early in 1921 the Sher-Gil family sailed for India, to settle down in Simla in a large house at Summer Hill. There, memory of the years of anxiety and difficulty were almost completely eradicated as the family relaxed in the comfort of their new home.

Marie Antoinette had a great love for western classical music: she saw to it that her children learnt to play the piano and the violin, and was keen to see that they develop their creative faculties. By the age of nine Amrita and her sister were giving concerts and acting in plays at the Gaiety Theatre, Simla's snobbish cultural centre. Because of the eagerness with which Amrita was drawing at the age of eight, a Major Whitmarsh was employed to teach her the art. The Major laid great stress on achieving an accurate likeness, and so made her draw the same subject again and again. After some lessons Amrita told her parents that it was a waste of time to continue. She subsequently attended classes held by Beven Pateman, a fashionable society painter, who worked only in pastels (a medium Amrita disliked); and she enjoyed the semi-professional atmosphere of the studio.

By the age of eight Amrita had become a serious withdrawn child, who preferred books to toys and the company of adults to that of children. She also felt her parents preferred her younger sister to herself and accused them 'I know Indu is your favourite, you do not care for me because I am ugly and I squint'. An operation removed her squint and partly restored her confidence in herself-but did not entirely remove her feeling of being less loved.

In 1923, a young Italian sculptor became intimate with Marie Antoinette. As her husband was an extremely jealous man she explained away the sculptor's presence by saying that he was helping Amrita in her drawing. Some time later the sculptor had to return to Italy and Marie Antoinette decided to follow him with the children. She told Umrao Singh that it was time Amrita and her sister received some exposure to Renaissance art and learnt Italian. Consequently in January 1924 Amrita was admitted into the upper class school of Santa Annuciata in Florence; but in a few months she rebelled against its orthodox discipline, describing it as an 'enormous, elegant but hateful school'. Since the sculptor was no longer interested in Marie Antoinette, it was decided to take the children out of the school and to return to India. Amrita sensed what had happened, and years later in Paris when a similar incident took place, she told her sister that 'mother is trying to make a scapegoat of me now, as she had done with the Italian sculptor'.

In Simla, despite Amrita's own opposition, she was put into a convent school. She disapproved of the compulsory church attendance and told her father that she was an atheist. From the convent she wrote a letter denouncing all religious practices, laying a special emphasis on the Roman Catholics whom she considered bigoted and ostentatious in their rituals. The letter got into the hands of the mother superior who forthwith expelled Amrita from the school.

In the following years Amrita kept herself occupied with painting, reading and playing the piano with great zeal. For Amrita Beethoven was not only a genius as a composer but also a man with great will power, strength and conviction. She would often quote what he was alleged to have said to the Emperor Napoleon, when reprimanded for not removing his hat and bowing to his Majesty: 'there will be many Emperors but only one Beethoven'. To her sister she would compare him favourably with 'your weakling Chopin and his romantic music'. However in her sensitive perception of the sadness within people she would herself demonstrate a certain type of romanticism.

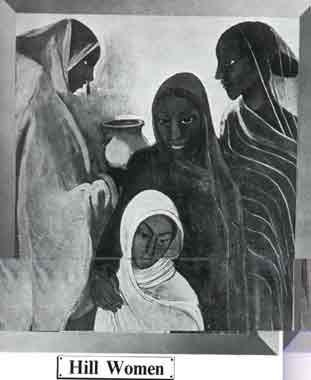

At the age of twelve, Amrita put down in her diary this description of a bride at an Indian wedding. 'She was very fair and there was an expression of weariness in the lovely liquid dark eyes. Her little finely curved and red hued lips seemed like drooping rosebuds and were sealed as if it were in silence eternal. - she seemed as if she guessed the cruel fate which had been meted out for her by the Rani and Rajah and her other rich but distant relations in whose hands she seemed a helpless toy.' In this piece of delicate writing is there not an uncanny similarity between 'the bride of liquid dark eyes' and 'rose hued lips' and faces in painting like Hill Women done in 1935 and The Bride done in 1940.

The Bride (1940)

The drawings and watercolours Amrita did between the ages of eleven and fourteen (1924 to 1927) are related to a growing awareness of herself. By 1927 Amrita had been in India for six years, yet the people and landscape in her drawings and paintings are entirely European. In her earlier work she draws with a thin tremulous line, wistful maidens naked and lost in forests. Later her characters (and here a strong influence of books and films manifests itself) and the women in particular are shown with their faces tense with suppressed emotion, either attempting suicide or threatening to stab the men they are with.

In 1927 Amrita's uncle, Ervin Baktay arrived from Hungary. He had started off his career as a painter but had given that up to study eastern religions and art and had become a renowned Indologist. Seeing Amrita's passion for drawing and painting, he suggested she draw from live models, which was something she had never done before. The models most readily available were servants like the sweeper and his family who posed for her. The assiduousness with which Amrita recorded what she saw impressed her uncle who encouraged her to do more. She would attentively listen to his criticism and told him later 'It is to you I owe my skill in drawing'. The process of making these drawings must have made a deep and lasting impression on Amrita for it was these faces, that, after her European academic training, haunted her and led her to return to her native land.

RETURN TO EUROPE-(1929 to 1934)

Amrita between sixteen and twenty-one years of age

In 1929 when she was sixteen years old, her mother felt it was time for Amrita to start an academic training in art: so the family set out for the capital of European culture, Paris.

In a matter of months Amrita had learnt to speak french fluently and with great ease adapted herself to the Parisian way of life. Her domineering mother took the girls to see 'good' theatre and concerts, and would arrange soirees of so called intellectuals, musicians and writers, at which she would present her daughters. Amrita detested these salon gatherings and stopped going to conventional plays and operas when she discovered the off-beat and avant garde theatres frequented by her artist friends.

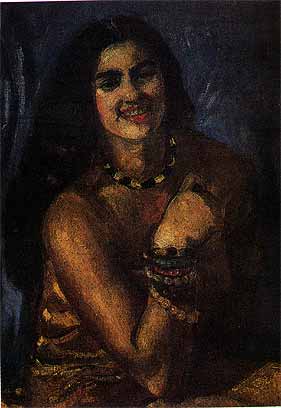

The dark corners and smoky cafes of Bohemian Paris opened up their secrets to a new and thrilled Amrita who entered them with wild abandon. Here she met creative and unconventional people, whom she identified with characters from the books she had absorbed during her period of moody introspection. Amrita now became the uninhibited vivacious and happy person, which she appears to be in some of her early self-portraits. This was a different Amrita, an extrovert whose life became an eternal round of parties, concerts, theatres, films and exhibitions. Wherever she went people noticed her Eurasian looks, were captivated by her exotic charm and struck by her intelligence and confidence.

Apart from this high living she painted and drew diligently, initially at the Grand Chaumiere under Pierre Vaillent and later at the Ecole des Beaux Arts under Lucien Simon. For a few months she was admitted to the Ecole Normale de Musique for piano lessons in which she was quite talented, but gave it up, saying that she didn't believe in being a Jack of all trades and master of none.

Amrita in a Paris Cafe in 1932

From 1930 to 1932, Amrita did hundreds of sketches and studies of male and female nudes, mainly in charcoal. In these academic drawings the volume is emphasised by shading, and the energetic sweep of the line creates heavy, massive figures. Also around 1930 she started working in oils for the first time, and during these three years produced over sixty paintings. Some of these are studies of models in the nude, a few are 'still lives' and a handful are landscapes; but mainly they are portraits and self portraits. The paintings have nothing remarkable about them except an academic competence, which was acclaimed in the Beaux Arts. Her painting Young Girls won the Gold Medal in 1933, leading to her election as an associate of the Grand Salon.

Amrita in

Paris 1931/32

Amrita in

Paris 1931/32

Though the self portraits are mediocre as paintings the personal image that Amrita projects is significant: she paints herself against a flaming red background, revealing her desire to assert the individuality of her character in a dramatic way. She painted with great speed, not giving much thought to what she was doing, and usually got carried away by the very act of painting.

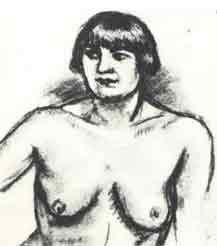

Charcoal Nude Study (1930?)

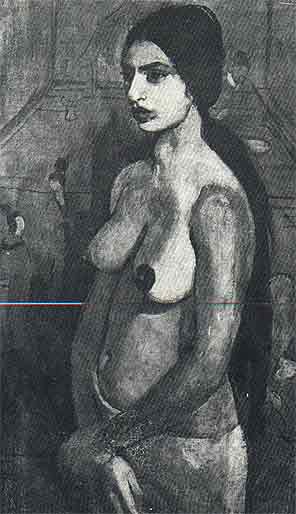

In 1933-34 Amrita's output dropped dramatically to about a dozen paintings. In some of them we find a definite change, a more sophisticated application of paint, and an introspective withdrawn mood in the figures. These paintings are Professional Model 1933, Study of Modelin Brown and Study of Model in Green 1934, which we shall briefly discuss.

Self Portrait -1935

Professional Model is a portrait of a middle-aged nude woman, weighed down with a melancholy which is not attributable only to her age but seems to be the anguished isolation of a big city dweller. The same woman has her downcast look and haggard slouch again emphasised in a Study of a Model in Brown, and is known to have been suffering from TB. Both these paintings suggest an emotional tone similar to the mood evoked in Picasso's blue period painting: the mood of big city-dwellers in a state of hopeless dejec-tion. In the Study of Model in Green a new dimension is added to the woman's expression of ennui by the application of a Cezannesque blue-green to the clothes.

Nude 1938 Woman at Bath 1940

The artist's mother disapproved of her daughter's Bohemian life style. She was keen that Amrita should settle down with some well-to-do respectable husband, and had in mind a particular young Indian whom she had recently met. Amrita was persuaded to become involved with him and they were engaged for a few months-until the girl broke it off, realising that she had nothing in common with him. This enforced liaison had a profound effect on her life, since she caught a contagious disease from the aristocrat. Even though she was cured of it by a cousin of hers, a doctor in Budapest, she lived always in fear that she might be disfigured for life. Almost in the way of avenging herself upon her mother's idea of an arranged marriage, she tended towards promiscuity and did not want for some time to be committed to a single man. She declares in a letter: 'I am always in love, but unfortunately for the party concerned, I fall out of love or rather fall in love with someone else before any damage can be done'.

Inevitably the consequences of this were that she became impetuous in her relations with men, bringing herself twice to the point almost of motherhood. In a mood of reaction she felt and wrote that perhaps a relationship with women may be more pure, and was drawn into an involvement with a pianist friend. Although not consciously, women often figured in her work, portrayed in their loneliness with their fears and secret longings... Yet at the same time she continued to search for a satisfactory relationship with men.

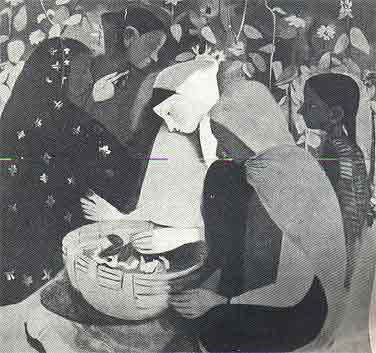

Painting women in a market

Amrita's attitude and response to contemporary art is ambiguous and puzzling. Although she was in Paris from 1929 to 1934, by which time the most important styles and movements of twentieth century art had come into being, yet she makes no reference to most of them. Her academic studies only took her through to the art of post-impres-sionists. Though she thought her work was never 'tame or conventional' she considered exhibiting in the Grand Salon a great honour. As she expressed it in a haughty and petulant letter written to the Simla Fine Arts Society in 1935 'I shall in future be obliged to resign myself to exhibiting them (her paintings) merely at the Grand Salon, Paris, of which I happen to be an Associate and the Salon de Tuileries known all over the world as the representative exhibition of Modern Art, and to which I have been invited to participate in the past, a distinction I may add that few can boast of.' This statement reveals how out of touch was her notion of modern art in Europe.

In September 1934 Amrita observed her new orientation when she wrote 'Modern art has led me to the comprehension and appreciation of Indian painting and sculpture. It seems paradoxical but I know for certain that had we not come away to Europe, I should perhaps never have realised that a fresco from Ajanta or a small piece of sculpture in the Musee Guimet is worth more than a whole Renaissance.'

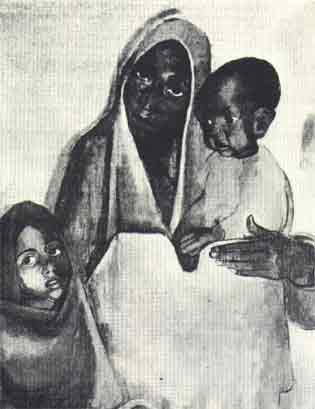

Mother India (1935)

Regarding her romantic desire to return to India she said: 'towards the end of 1933 I began to be haunted by an intense longing to return to India, feeling in some strange inexplicable way that there lay my destiny as a painter.' In the same article 'Evolution of My Art' she naively agreed with her professor's comment that 'judging by the richness of my colouring, I was not really in my element in the grey studios of the west, that my artistic personality would find its true atmosphere in the colour and light of the east.' She seemed to forget that fifty years before, painters had left their studios to capture light and colour of the open air and that; her own Paris paintings are as grey as the 'grey studios of the west.'

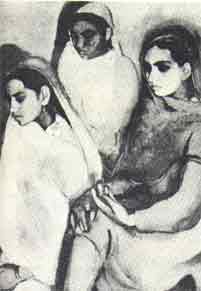

Three Girls (1935)

During her stay in Europe Amrita went every year to Hungary: on the one hand to get away from Paris and the French (for whom she had no great love) and on the other to be amongst her own people and the Hungarian country side. For her Hungary was a country of passion and beauty and she loved its 'honest' simple peasant folk, their language and their culture.

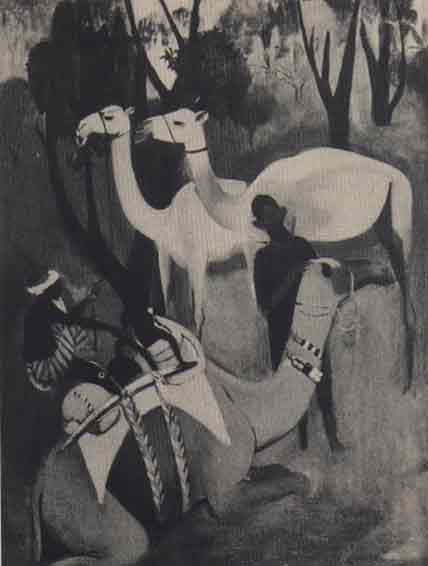

Camels

Hungary has long been considered by Western Europe to be a backward country, outside the main stream of European culture. Ever since the rise of Hungarian nationalism at the end of the 18th century, a continuous search and assertion of the national identity was a dominant factor in its history. At the turn of the twentieth century there was great activity on the cultural front, where artists and writers were in close contact with the French. Although an element of 'catching up with the west' partly determined their approach, the writers were aware that they were heirs to a great Hungarian literature. In the words of their first modern poet, Ady, they were to create 'the new song of the new epoch'. Ady also attempted to integrate the latest European intellectual trends with the Magyar tradition: his poetry, a forest of symbols, is pierced by the beat of the western metre and old Hungarian verse.

A Hungarian

Peasant 1938

A Hungarian

Peasant 1938

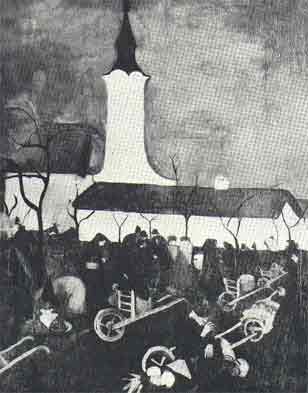

Scene of an Hungarian Market

Amrita was a great admirer of Ady, considered his poems her Bible and identified herself with a number of aspects of his life. M. Szaboksi writes 'Ady's poetical world is a self contained world: themes include revolutionary heroes and movements of Hungarian national history, the back-wardness of Hungary-the shocking visions of the Hungarian fallow land-thousand and one aspects of love; images evoking death, fleeting time, fear and solitude, verses that convey the restlessness, the strain and worries of the big modern city dweller-and the proclamation of a historic mission'. Amnta had little interest in revolutionary heroes and the movements of Hungarian national history. It was the theme of death and fleeting ~ime that most obsessed her and these sentiments were transposed on to her paintings.

In Paris the products of modern art had emerged from a society where the historical development of capitalism had reached its imperialist phase. Many of the experiments of modern art were related to technology and the forms often reflected the mechanisation and dehumanisation of the society. All this was alien to the atmosphere in which Amrita had been brought up. The 20th century became her own experience only when she went to Paris.

That is not to say that Amrita was entirely oblivious or reactionary to what was contemporary and avant-garde. She read avidly and admired poets and writers like Baudelaire, Verlaine, Dostoevsky, Thomas Mann, James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence and modern Hungarian writers like Endre Ady and Dezo Sazbo. Her taste in literature definitely suggests a tendency towards identification with the introspective and psychological elements in novels. Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, The Idiot and The Possessed, Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain and Marcel Proust's Swans Way and Remembrance of Past Things were amongst her favourite novels.

Amrita returned to India because her experience in a metropolis, after the initial -excitement had died, was painful. Her predominantly romantic outlook caused her to reject the enormous changes taking place in art and society. Her formal pre-occupations were thirty years behind the times; and she probably realised that it would have been impossible for her to develop and contributed anything of significance to modern art in Paris. In India she knew there was nobody of importance in the field of art much needed to be explored and her sense of mission urged her to return in quest of an identity. A few years later she proclaimed, 'Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse and many others, India belongs only to me.

RETURN TO INDIA

At the end of 1934 Amrita returned to India. After spending some months in the palatial Majitha house, her ancestral home in Amritsar, and at her uncle's enormous estate in Saraya, Amrita descended upon Simla. With the coming of summer the idle elite of Indian society had comfortably settled in their summer capital. Overnight Amrita became the focus of attention: her name was included in invitations to all the parties thrown by the complacent Rajas and bureaucrats who desired her company for titillation and amusement.

Resting 1939

Amrita's attitude to those of her own class background is ambiguous, and in practice her actions often contradict her words. After the initial thrill of discovering her power to tantalise and embarrass this westernised elite, she realised that their conservatism and demeaning respect for the British would in no way help her own understanding of India. However her class background, and the fact that she was both a woman and a painter made it impossible for her to reject them entirely. The more conservative products of an Oxford/ Cambridge education were drawn to the civil service and described by Amrita as a 'dull, uninteresting and scandal-mongering crowd.' Amongst the more intellectually daring group she found those companions who were to remain close to her until her death. She responded to their caustic humour only because they were conversant with the literature that interested her, and had some knowledge of the movements of modern art. Strangely perhaps, it was the Muslims rather than Hindus who accepted her licentious behaviour and to whom she felt most attracted.

Story Teller 1937

Before the end of the summer season Amrita had caused an enormous stir in the art world, with the unprecedented action of returning a prize to the Simla Fine Art Society because they had rejected what she considered her best work and given the award for an inferior painting. Had she returned her gold medal to the Paris Salon she might be said to have taken an anti-establishment stand; but instead she proclaimed that she would in future only exhibit there!

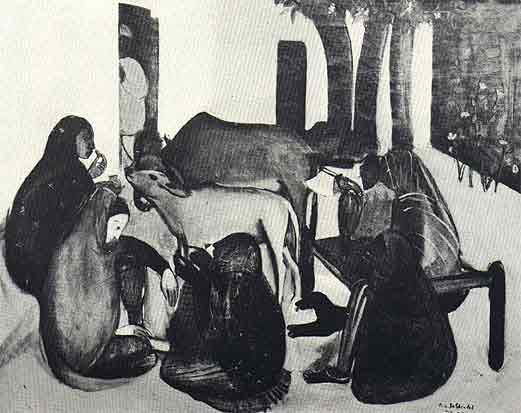

Village Group 1938

Amrita always painted during the day without the help of artificial light. Only on rare occasions would she allow people to see her work whilst it was in progress. Wearing a large rough painting coat and with her hair pulled tightly back, she completed the stark and austere atmosphere which prevailed in her studio. At the fall of day she would transform herself into the image of a glamorous socialite, dressing and making herself up elaborately. But on her return from the evening's entertainment, she would again return to the canvas and spend some time looking at it.

In her first year in India she painted many portraits of her family and friends, the most notable being The Three Girls. In the same year, during the months of high living she produced sentimental and romanticised versions of Indian poverty in paintings like Mother India, The Beggars and Woman with Sunflower. Her real artistic mission, she proclaimed, 'was to interpret the life of Indians and particularly the poor Indians, pictorially'. But she was interested in them only as aesthetic objects 'strangely beautiful in their ugliness'. For her the poverty of India was beautiful, and the people who barely survived inhuman and primitive conditions, merely exciting images. She felt that conditions in India could not change and that poverty was a permanent feature. For her the masses were like silhouettes and dumb silent images of infinite submission and patience 'who would fatalistically accept their lot for time immemorial.' One day she nonchalantly told a friend that if there were no poor and destitute people in India she would have nothing to paint.

With the end of the summer season and the approach of winter came time for reflection and concentration on her work. During November and December she executed two of her most important paintings: Hill Women and Hill Men (the latter she originally called villagers in winter). Although in Hill Men Amrita created monumental forms, which impart a sense of dignity to the figures, yet there prevails a passive, melancholic mood in the static images.

Almost the whole of 1936 passed in an uneventful fashion devoid of work that came near the level of Hill Men and Hill Women. This inconsistency in the quality of her painting is present in all the phases of her work. She seemed incapable of sustaining the intensity and tension of the mood created in her best works. (She did on an average 12 to 15 paintings a year). Impatience would make her leave a work in which she had lost interest. As a consequence much of even her best works are left unresolved and poorly executed. She was aware of these lapses and wrote in 1940 'My sense of form on the other hand is developing only now and still has a strong tendency to evade me. It very often happens that I grasp it only for a short period and only sections of my painting are good as a consequence.

For purely financial reasons she did a large number of commissioned portraits which she disliked intensely. Very few people were interested in buying her other canvases, which she priced at an exorbitant rate for those days. She only enjoyed doing portraits of people whose faces she liked and some of' these faces become an important constitutive element in her compositions. In the commissioned portraits painted between 1935-38 there is a change in the handling of paint, which corresponds, to the development in her own work. She moved from the modelling of the face in terms of light and shade towards more simplified flat planes.

In November 1936 Amrita arrived in Bombay which was the first stop on an important tour to the south. In this city she met Karl Khandalavala, who was the first person to attempt to understand her work and who was later to become a great champion of it. This young art critic's specialisation was in miniature paintings and in the works in his small collection and those available at the Prince of Wales Museum. Amrita discovered the richness and variety of the Rajput and Basohli miniature painters. She was dazzled and delighted! A seed had been sown. At the present moment she could not use such pure brilliant colours and some other discovery was needed, for her palette still consisted of the cool stone colours we find in paintings like Hill Men. Then came Ajanta and Ellora! She exclaimed 'Revelations. Ellora magnificent. Ajanta curiously subtle and fascinating-I have for the first time since my return to India learnt something from somebody else's work.'

In South India she went to Cochin, Trivandrum, Cape Comorin and Madurai.

She visited temples both for sculpture and to see 'active manifestations of

religion' also discovering frescoes in obscure places (Mattancheri) and seeing

the 'subtle and forceful' Kathakali dance drama. The sight of the semi-naked

black bodies of the south Indians draped predominantly in white against a

background of rich emerald green vegetation made a strong visual impact on

her. She was so eager to paint this impression in terms of the form she had

been so excited about in Ajanta that while at Cape Comorin she executed

the 'Fruit Vendors.'

However it was not until her return to Simla that she painted what has often been called her South Indian Trilogy: The Bride's Toilet The Brahmacharis and South Indian Villagers going to Market. She later described The Brahmacharis as the most difficult thing she had ever done; but she seems to have derived a sense of satisfaction from it, for she asks in a letter- 'don't you think I have learnt something from Indian painting?' (Karl Khandalavala, 15-6-'37). That she was not concerned with representing specific types of Indians is demonstrated in that she was content to use Pahari and even Sikh models for the Trilogy. In her paintings, entitled Hill Men and Hill Women, there is nothing, which particularises a definite ethnic type. She was concerned with developing a certain personal facial type with whose expression she identified her own feelings. In the large-eyed, dark and angular faces with their pouting lips (which can be seen in much of her work until 1937) there is even a vague reminder of the way she herself used to make up.

At this point there is a startling change in the artist's development. Perhaps

it was

because she felt incapable of sustaining the tension of the Brahmacharis,'

or she may have realised intuitively that the influence of Ajanta was an artistic

impasse; or may be it was just her own inconsistency. Whether it was for one

or a combination of all of these reasons, she now painted two small pictures

simultaneously with the execution of one of her largest compositions, South

Indian Villagers going to Market. In these she delibera-tely eschewed the

monumentality of her trilogy in favour of parrot-like figures, sitting at

their ease in a courtyard, painted so as to convey a sonorous modulation of

colour and an unctuous texture. In April 1938 she wrote to Karl, 'I don't

know whether it is a passing phase or a durable change in my outlook but I

see in a more detached manner, more ironically than I have ever done. Less

'humanely' if you like to put it that way but also less romantically. That

is why at the moment I am fonder of the Moghuls, the Rajputs and the Jams

than of Ajanta.'

From January to May 1938, she painted at Saraya: Elephants Bathing in a Green

Pool Red Clay Elephant and The Verandah with Red Pillars and at Simla, Hill

Side, Hill Scene and Village Scene. Of these she said, 'these little compositions

are the expression of my happiness and that is why perhaps I am particularly

fond of them.'

From this period onwards, the figures in Amrita's paintings were either represented as small caricatures placed in a landscape or they physically take up the whole canvas and their emotive expressions and gestures became the raison d'etre of her work.

In June 1938 much against her parent's wishes, Amrita left for Hungary to marry her cousin Dr. Victor Egan. She was over twenty-five and wanted to be independent of them, but could not sum up the courage to live by herself because of the social and a lack of income with which to support herself. There were lots of well to do Indians who were keen to marry her, but she was apprehensive of being an 'ideal' wife, and held the view that she could not be a mother as well as a painter. She felt that Victor was the only person who not only understood her, but accepted her as she was.

After an absence of almost four years, Amrita spent a whole year in Hungary.

Most of the time she lived in small places in the countryside and in the mediaeval

village of Zebegeny where a number of 'naive or folk artists' of the populist

school had settled.

Amrita was greatly interested in the work of these 'naive' artists as well

as in the work of

Istvan Szonyi, leader of the populist school. As there are some interesting

correspondences

in attitude between Amrita and Szonyi, as well as a similarity in some of

their paintings

I shall quote briefly from L. Newmeth's book Modern Art in Hungary.

'Zebegeny was his Tuscany, his refuge, a virgin land in which human beings could still live together in harmony and simplicity. He tended to idealise the peasants lot, imagining it to be an idyllic existence in which man could retain his old relation to nature. He deliberately rejected the intellectual and analytical approach of the various established styles for he felt that it was an essential trait of the Hungarian character to be un attracte& to speculation. For this reason he was not interested in a rational analysis of the modern possibilities of composition and representation of space.'

The other artist that Amrita discovered in Hungary was Breughel the Elder

for whom she developed a regular passion. She was conscious that her painting

Hungarian Market

Scene was 'rather Breughelesque'.

The paintings she did in Hungary are entirely European in their colour, mood and sensibility; yet there is a marked change from her Paris work. The people are observed with sympathy but without that overwhelming melancholy of the late Paris phase. This is worked out formally in the flat treatment of the surface, a simplification that was also influenced by Indian miniatures. In Hungary Amrita began a canvas, large in size and stark in the simplicity of its formal conception. It is a painting of Two Girls. A dark girl and a light girl. But it is more. It is a picture loaded with overtones of both a personal and a social nature, and it touches upon the 'quick' of Amrita.'s consciousness. It is a painting of the physical and emotional longing of two women for one another. Yet it is also a rejection and misunderstanding-the rejection of an impossible desire, not by either individual but by invisible forces within themselves which neither understand. The white woman stands erect and coolly unabashed, her legs frankly apart and her whole presence suffused with the confidence which her cultural background allows her. The black girl is no less beautiful, in fact she has a charm, which is all, her own, but she seems to exist on a different level of consciousness. As she sits demurely on the edge of a chair with a cloth pulled tightly around her, she seems to be the epitome of a feudal Indian woman. It is as if the dynamism of Greek sculpture had been suddenly brought into juxtaposition with the static simplicity of an ancient Egyptian figure. A shock of awareness. Transposed to a structure in which the boldness of its simple yet powerful design seems to be searching for a synthesis between dark and light-between black and white.

Yet there is nothing simplistic in this painting. Nothing dogmatic or mechanical in Amrita's perception of the relationship.. She has touched upon something, which no other modern Indian painter has seriously tried to understand in its entirety. Perhaps she was in a better position to see it than anyone else for it is in the nature of the relationship between women that we find the most poignant expression of this racial confrontation Amrita was a woman who knew about women and who, in herself, embodied the conflict between the two cultures-east and west.

In June 1938 Amrita and her husband fled from Fascist dominated Hungary and

the impending threat of war. Though Amrita was opposed to Fascism this was

not because she held any progressive political views, but because her strong

sense of justice deplored the suppression of individual freedom and the domination

of weak countries by strong. Like most artists and intellectuals she thought

first of her own interests. She wrote, 'it is dreadful to think of Paris in

German hands but what preoccupies me still more is what is going to happen

to modern French art and the younger artists.'

BACK IN INDIA AMRITA'S LAST YEARS 1939-41

The couple reached India via Ceylon and on their way to Simla they visited Mahabalipuram and Mathura. At the latter she saw Kushan sculpture for the first time and she proclaimed-'I was positively stunned and have straight away become a votary of Mathura art to the exclusion of all the other and later schools.' Had she discovered Kushan art at an earlier period she might have been able to use its bold austerity in het work. But now she was involved in exploring the colour and atmosphere of the miniatures.

The village of Saraya near Gorakhpur is no different from the thousands of other villages scattered over the populated state of Uttar Pradesh. People still live there in conditions of abject poverty and backwardness. The villagers' homes are primitive mud huts, without proper drainage or sanitation, and to this day there is no electricity in the village. The landscape around Saraya is generally monotonous as the dry flatlands spread for miles in all directions but a continuous screen of dust is raised throughout the year by an endless trail of bullock carts bringing cane to one of the largest sugar factories in India. The rumble of carts is broken only by the factory siren every eight hours as the three thousand workers go through their daily grind. Life is not idyllic except behind the high walls of the factory owners estate. The Majithia's vast property is dotted with palatial houses amidst spacious gardens, shaded and kept cool by large trees. At the end of the gardens, surrounded by a white wall stands a lonely remnant of feudal architecture-the white dome.

This pleasant pastoral scene forms the backdrop for several of Amrita's paintings for instance The Ancient Story Teller, Elephants Promenade and The Swing. From these paintings one would never imagine that (behind the dome) the gigantic chimney of the sugar factory thrusts its way forcefully into the sky,-one would never conceive what a hum of activity is hidden by the silent white walls.

Of course there is no suggestion that Amrita should have depicted the exploitation or suffering of the workers but the sharp contrast between the two brings into focus the fact that Amrita was involved in portraying a view of feudal India. The harsh realities of modern life in this country, even though on her very doorstep, were of no interest to her.

For Amrita's life at Saraya had two facets. On the one hand Saraya was a haven where she and her husband could set up a home in the comfortable lap of the Majithia house hold. There she could relax, go for long horse rides, and take part in elaborately organised tiger hunts on the back of elephants, and, in short indulge herself in a life of feudal extravagance.

On the other hand there was no stimulating company, no one with whom she could hold an intelligent conversation. No opportunity to expand her ideas. She felt trapped and suffocated as an 'unutterable lassitude and vague chemeric fear' descended upon her at the end of 1940. In the last year of her life she said she felt impotent and dissatisfied; that there were elemental forces at work, disrupting and throwing things out of equilibrium. She was gripped by a Sort of fear whenever she thought of painting again.

Amrita did very few paintings in 1941 in the last year of her life. Four

of her most important works were in fact done in the first half of 1940-The

Ancient Story Teller, The Swing, The Bride and Woman Resting on Charpoy.

The latter three paintings are about women. During her stay in Saraya Amrita

had become very friendly with some of her female relatives. She would often

while away the hours in the company of a group of women, which included both

servants and mistress. This contact with the cloistered life of traditionally

oriented Indian women made her aware of their social and psychological problems.

Woman Resting on Charpoy seems to exude a quiet perceptive understanding of

the psychology of the feudal Indian woman. We sense that beneath her apparently

restful pose there is turmoil of suppressed desires. We are made to feel a

shocking intimacy with the woman by her erotically suggestive pose and by

the tilted charpoy which puts us immediately above her. Yet though she seems

to lie passively, there is a restless movement in the woman, which suggests

the painful birth of an awareness. A consciousness of the restraints imposed

on her by her social environment.

In September 1941 Amrita and her husband finally managed to get away from the claustrophobic Saraya estate and went to settle in Lahore. Although Lahore had a number of conservative people, there were numerous students, writers and artists who held pro-gressive views and were sympathetic to the nationalist struggle. They created an intellec-tually lively atmosphere and brought out a number of magazines and journals. Amrita enthusiastically participated in the cultural life of the city, gave talks on the radio and met a number of interesting people.

Amidst the excitement of her new environment she started her last work. It is a very matter of fact view of a court yard seen from above. In this painting she seems to be even more involved in putting down her love for India in a direct and simple form. While moving away from her tendency of decorative formalism, she seems to be striving for a synthesis of content and form and attempting to resolve the dialectic between art and life.

But both this synthesis and the painting remain unresolved. Amrita died suddenly on the 5th of December 1941 before she had even reached the age of twenty-nine.

I would like to thank Dr. Victor Egan (Amrita's husband); Mrs. Indira Sundaram (Amrita 's sister); and Mrs. Helen Chamanlal (a close friend of Amrita) for giving me a great deal of valuable information about Amrita. Without their generous co-operation this article would not have been possible.

We present an article from the autobiography of the great writer Khushwant Singh about his relationship with Amrita.

Truth, Love and a Little Malice

Khushwant Singh

Two people whom I met in these years in Lahore deserve mention. One was the

painter Amrita Shergil. Her fame had preceded her before she took up residence

in a block of flats across the road from ours. She had recently married her

Hungarian cousin, Victor Egan, a doctor of medicine who wanted to set up practice

in Lahore. Amrita was said to be very beautiful and very promiscuous. Pandit

Nehru was supposed to have succumbed to her charms; stories of her sexual

appetite were narrated with much slavering of mouths. She had visited Lahore

earlier and stayed at Falettis Hotel to find a suitable apartment. She was

said to have given appointments to her lovers, three to four every day with

intervals of a couple of hours in between. They came, did their job and were

dismissed as soon as it was over. My friend of Government College days, the

diminutive Iqbal Singh who was then a producer in All India Radio, was said

to be her last visitor of the evening. He had the limited privilege of ministering

to her needs while she slept. I didn't know how much truth there was to gossip

of her being a nymphomaniac, but I was eager to get to know her. I did not

have to wait very long.

It was summer. My wife and six-month-old son had gone up to Kasauli to stay

with her parents. One afternoon when I came home for lunch I found a tankard

of beer and a lady's handbag on a table, and a heavy aroma of French perfume

in my sitting room. I tiptoed to the kitchen to ask my cook who it was. 'I

don't know,' he replied, 'a memsahib in a sari. She asked for you. I told

her you would be back for lunch. She looked round the flat and helped herself

to the beer from the fridge. She is in the bathroom.'

I had no doubt it could only be Amrita Shergil. And so it was. She came into

the sitting room and introduced herself. She told me of the flat she had rented

across the road and wanted advice about carpenters, plumbers, tailors and

the like. I told her whatever I knew about such people. I tried to size her

up. I couldn't look her in the face too long because she had that bold, brazen

kind of look which makes timid men like me turn their gaze downwards. She

was short and sallow complexioned (being half-Sikh, half-Hungarian). Her hair

was parted in the middle and tightly bound at the back. She had a bulbous

nose with black heads showing. She had thick lips with a faint shadow of a

moustache. I told her I had heard a lot about her paintings and pointed to

some watercolors on the wall, which my wife had done. 'She is just learning

to paint,' I said by way of explanation. 'That's obvious,' she snorted. Politeness

was not one of her virtues; she believed in speaking her mind, however rude

or unkind it be. A few weeks later I had another sample of her rudeness. I

had picked up my wife and son from Kasauli and taken them up to Mashobra.

Amrita was staying with her friends the Chaman Lals, who had rented a house

a little above my father's. I invited them for lunch. We were having beer

and gin-slings on the open platform under the shade of the holly-oak. My son

was in a playpen learning to stand on his feet. Everyone was paying him compliments:

he was a very pretty little child with curly hair, large questioning eyes

and dimpled cheeks. 'What an ugly little boy!' remarked Amrita. Others protested

their embarrassment. My wife froze. Amrita continued to drink her beer without

concern. Later, when she heard what my wife had to say about her manners and

that she had described her as a bloody bitch, Amrita told her informant, 'I

will teach that woman a lesson. I'll seduce her husband.'

The day of seduction never came. When we returned to Lahore, my wife declared

our home out of bounds for Amrita. Some months later common friends told us

that Amrita was not well. One night a cousin of hers came over to spend the

night with us because Amrita was too ill to have guests. He told us that she

was delirious and kept mumbling calls at bridge - she was an avid bridge player.

Next morning we heard she was dead. She was barely thirty-one.

I went over to Egan's apartment. Amrita's old, bearded father Umrao Singh

was in a daze and her mother hysterical. They had just arrived from Summer

Hill in Shimla and could not believe that their young, talented daughter was

gone forever. That afternoon a dozen men and women followed her hearse to

the cremation ground where her husband lit the funeral pyre. When we returned

to Egan's apartment, the police were waiting for him. England had declared

war on Hungary as an ally of Nazi Germany. Egan had become an enemy national.

He was lucky to have been taken into police custody.

It took some time for Amrita's mother to get the details of her daughter's

illness and death. She held her nephew and son-in-law responsible. She bombarded

ministers, officials, and friends (including myself) with letters accusing

him of murder. Murder, 1 am certain, it was not. Carelessness, I am equally

certain, it was. My version of her death came from Dr Raghubir Singh, then

a leading physician of Lahore. He was summoned to Amrita's bedside at midnight

when she was beyond hope of recovery. He believed that she had become pregnant

and been aborted by her husband. The operation had gone wrong. She had bled

profusely and developed peritonitis. Her husband wanted Dr Raghubir Singh

to give her a transfusion and offered his own blood for it. Dr Raghubir Singh

refused to do so without finding out their blood groupings. While the two

doctors were arguing with each other, Amrita slipped out of life.

Many people like the art critic Karl Khandalawala, Iqbal Singh and her nephew,

the painter Vivan Sundaram, have written books on Amrita. Badruddin Tyebji

has given a vivid account of how he was seduced by her (she simply took off

her clothes and lay herself naked on the carpet by the fire place). Vivan

admits to her having many lovers. According to him her real passion in life

was another woman.