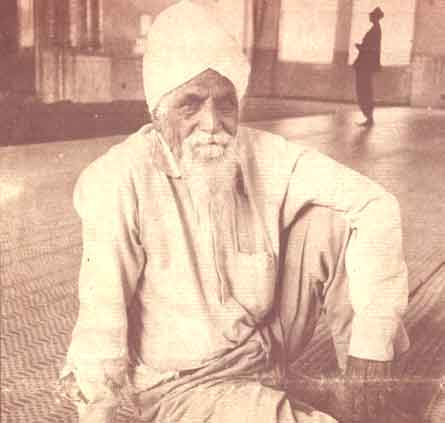

Hari Singh Bansal, a very simple man who used to be seen on the streets of Nairobi, with an aura of a saint, deep in thoughts and in a divine trance.His simple life and dedication to his work can be seen in most temples, mosques and gurdwaras in East Africa and some in U.K.

The following is an article written by an african journalist/columnistWade Huie of the Kenya Daily Nation on 25th November 1977.

"Tranquil life of an Artist and Workman"

AMID the helter-skelter of the kiosks, retail market and country bus stops in Eastlands a turbaned, white bearded man quietly works.

Oblivious to the pandemonium about him, he chisels, sculpts, plasters and points on an ornate structure. While he creates, his face, paradoxically, reveals both a deep tranquility and a keen intensity.

Such profound concentration is the trademark of the work of Hari Singh Bansal, Kenya's most versatile Asian craftsman. Architect-mason-carpenter-sculptor-painter all rolled into one, he is currently working at Landhies Mosque (below)across from the retail market; he is designing the bora bhari, the front entrance to the mosque, where worshippers remove their shoes before entering.

Hari Singh Bansal on the parapet of the landhies mosque

But

Hari Singh doesn't just work for Muslims. Sikhs, Hindus and Gujaratis also have

often called on him. To mention a few of his creations: the Landhies Mosque itself,

the Pangani Mosque, the art work at the Ram Mandir in Eastleigh, the Makindu Sikh

Temple, the Kahawa Mosque and a series, of life-size religious statues at the

Ramgharia Railway.

"Working for religions other than my own doesn't bother

me," says Hari, pausing from dressing up a minaret. "In essence all

religions are the same, in that God is one. So I'll do work for anybody with the

same heart."

For most buildings on which he works, Hari Singh

designs the architectural plans as well as doing all the artwork. He also directs

labourers in construction.

The 78year-old Sikh has no plans to slow down either.

After finishing at the mosque, he plans to construct some statues and fountains

et a private home and later on another mosque, in Makindu.

Hari refuses

to haggle over charges for his services, but will take whatever his employer will

give him. "I love my work," he says. "When I'm working for religion,

I know that God is near me and is pleased. This makes me forget about the world

and I become lost in my work."

"My work keeps my life going. If

I quit, I know that my body and mind will deteriorate and I will die."

Whether true or not, Hari Singh is certainly in excellent shape; his square shoulders,

thick wrists and sturdy hands belie his age. "I'm suffering from nothing,"

he says, "except I did have to get some false teeth."

Hari Singh

was born in the little village of Jullunder, India, in 1899. He started learning

his craft at 20, when he became an apprentice to his father, a designer also of

mosques and temples. It was 10 year before Hari was sent out on his own. He then

trekked about India and Pakistan, painting and sculpturing.

In 1950 Hari came

to Kenya to visit friends and decided to stay. "With all the poverty in India,

I found Kenya to be a gold mine," he recalls. "Also, I saw my skill

was needed here, and I liked the country's cool weather." -

One of Hari's

first painting of Guru Nanak, a Sikh leader was so popular that there were soon

other requests for painting. But to ensure a more regular income, Hari joined

a Nairobi Painting firm and started doing the art work for signboards, many of

which still front dukas in town.

But with his reputation spreading, Hari

soon found that he was spending more time designing places of worship than in

doing signboards for fish-and-chips establishments or chemist shops.

The soft-spoken

Sikh now works on his own. Married, he has two sons, one a carpenter, the other

an accountant. If he has any spare time, Hari prays, meditates, feels his 100

beads, or reads the Granth Sahib, the Sikh 'Bible'.

Some of the greatest praise for his works, says Hari, comes from Africans, who probably do not fully understand the religious significance of his art. Hari himself strongly appreciates African Art. "African artists are very good at depicting natural landscapes and their people's daily life," he says.

Besides earning a living,

what is the main purpose of his work?

"To bring happiness to people,

he answers. Also, when I'm gone, my buildings will serve to remind my friends

of me."

Hari surprisingly plays down the aesthetic aspects of his skill. "A fellow interested in doing my work must first believe in God," he declares. "Secoond, he must be willing to turn away from the modern world, to be able to keep only one thing in mind: that he's working for God."

Hari's only real worry, he says, is that no one in Kenya is learning Hari's trade. "I am willing to teach anybody who is willing to learn," he says, stroking the two long strands of his snowy beard. "It would greatly help me, for working alone takes a lot of time and keeps me from starting other works. If I can teach somebody my art before I pass away, my mind and heart would be relieved."

For Hari Singh's ways to pass away would indeed be a big loss to the richness and diversity of art in Kenya.

It is indeed a great loss to the art world as a successor to this great artist has not been found since his death in the UK, a few years after the above article was written.

We present some of his 'available' art work

A painting of Guru Gobind Singh Meditating on the Hem Kunt in his previous life. Painting used for a post card.

Joga

Singh being refrained from entering the house of a prostitute by Guru Gobind Singh

disguised as a watchman.

A gate built by Hari Singh Bansal on the occasion of the Hola Celebrations in Nairobi and the holy visit of Satguru Partap Singh Ji in 1959

A gate built and decorated by Hari Singh on the occasion of the visit of Princess Margaret to East Africa in the early 60's.

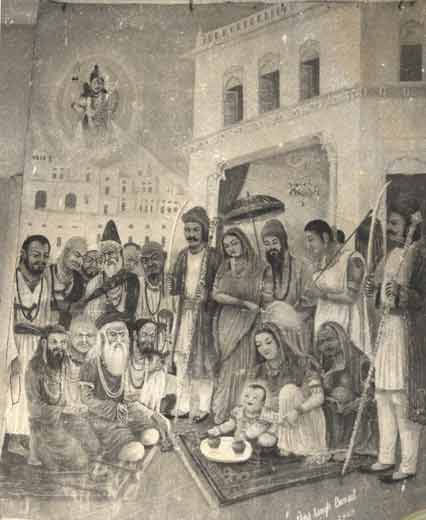

Painting made in 1962 of Balak Guru Gobind Singh laying both his hands on small bowls brought by Muslims and Hindus to test the Guru to which religion he was inclined to. By putting both his hands on both bowls the Guru indicated that both religions were same to him and he was neither Hindu nor Muslim.

Guru Gobind Singh with his four Sahibzadas

Guru Hargobind blessing Mata Sulakhni with 7 sons

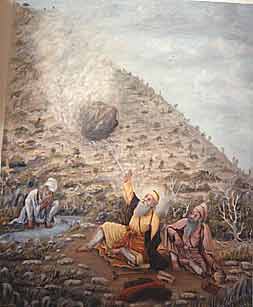

Guru Nanak stopping the stone thrown by Wali Kandhari. The episode of Panja Sahib

An imaginary painting of Lord Krishna and the Gopis.

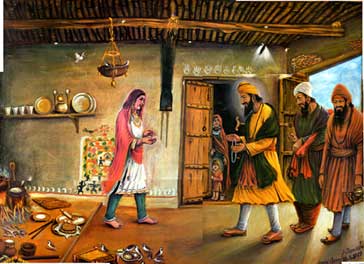

Bebe Nanki receiving Guru Nanak when she was making 'rotis' and wanted her brother to come and eat. Guru Nanak was at that time many hundreds of miles away but Bebe Nanki's plea for her brother brought Guru Nanak miraculously to her doorsteps.