SERENADE

On

scarlet roadside we stand with our eyes fixed on the sombre attic window which

opens not! Our sweet mistress named Lost History lifts not her veil! Time moves

not in gear reverse! Providence grants not serendipity to capture scenes past!

Our doleful ditty draws not response from La Belle Dame Sans Merci! In vain we

await a silver lining in cloudless sable! Wrench grows! Heart yearns for union

with merry mermaid!

Lo! Firmament splits! Down descends blithe spirit carrying

in its trail comment serene penned by McQueen.

While the Stars twinkle on the

firmament, non-sparkling Voids separate them from one another. While Hawks soar

in high sky, Snakes lie cramped in dingy crevices of the world.

History is

a record of collision of Titans and Pigmies, Swans and Ravens, Good Samaritans

and Heroes, Blood-Donors and BloodSuckers, Saviours and Killers, Healers and Cutthroats,

and Sacha Patshahs i.e. True Kings and Jhutha Patshahs i.e. FalseKings.

As

soon as Villains transform themselves into Heroes, global chaos will transform

into soothing cosmos.

But the long-awaited promised Millennium thus far remains

a vain dream.

No alchemist provides the philosopher's stone, which would gild

the iron shoes of sheep that graze pastures on slopes of valleys verdant and broad.

Pages

of history outpour more blood than salubrious herbal essence. Villains outnumber

Heroes.

We should love to inhale the part of history, which breathes healthful

fragrance.

In his Ramkali ki Vaar (M5) preserved in Guru Granth Sahib, the

third Guru Amardas makes a rhapsodic assertion:

'' Babanian kahanian put

sput karen!"

(Tales of glorious ancestors transform sons into dutiful

sons!)

It would seem that the discovery and joyous reading of pure part of

history would necessitate the expunction of the villainous part of it. To arise

as heroes, more than anything else we must know the history of heroes but it is

also necessary to know the negative performance of villains in the past so that

we should be able to eschew ugly deeds which people execrated in the past and

which they will execrate in the future too.

In our effort to sublimate our

lives, while we should select, accept and pick the gold in history, we should

identify and reject the dross.

Richard Wilson warns in the Preface to Lives

of Great Men published in 1911 in London that (as a binding onus on him) a great

biographer rivets attention on the 'crowded hour of glorious life' which won for

a man or woman a name to be remembered. In life there are great moments and small

moments. Maximum benefit accrues from concentration on momentous moments of lives

of great men.

Sir John W. McQueen's work is free from rigmarole.

McQueen

named his work The Kingdom of The Punjab - Its Rulers and Chiefs. However,

we have changed the title to Heroes and Villains of Sikh

Rule.

While creation of history is an arduous pursuit, preservation

of history is a rewarding job. If we do not learn lessons contained in available

annals, we shall be condemned to repeat the calamities, which we suffered in the

past. Our apathy to history incapacitates our visualisation and orientation of

forthcoming events. Study of past situations equips us to find mutatis mutandis

remedies to our present problems.

Loss of history due to negligence or accident

or prejudice remains a serious disadvantage.

Sir John W. McQueen completed

this work in 1894. Then his manuscript compilation comprising biographical

matter and pictorial representations slumbered in some niche for full sixteen

years. In the meantime McQueen passed away. On 1st May 1910 General Charles Pollard

contributed a short Foreword to late McQueen's work.

On 13th February 1994

we walked into the London's elfin grotto known as National Army Museum where we

fumbled for and found amid fervent jubilation McQueen's treasure chest.

From

1894 to 1994 teams of scholars from India came to United Kingdom, watched half-naked

men and women strolling and bathing on sun-lit beaches, delivered tall speeches

in lofty halls hired for them by seekers of fame and glory and returned to their

native country to tell their fellows the tales of 'research' picked by them from

domed British vaults. We wonder why the Providence reserved for us to unearth

and present to the world scholars the rare historical monument which had been

bequeathed by McQueen for detectives and diviners who would sniff at scrolls buried

very deep in valleys weird and enchanted.

O Cleo, on scarlet roadside we stand with gaze focused on sombre attic window! O beloved Muse, lead us to the treasure-troves buried under groves on brinks of rills or in burrows drilled in old hills. Amen!!

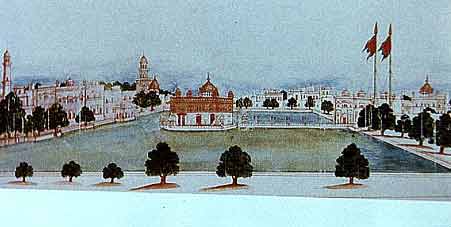

Amritsar,

the sacred city of the Sikhs, though boasting no great antiquity, is most picturesque

and striking.

The Sikhs may be described as dissenters from Hinduism bound

together by military ties: much of the ceremonial and formalism of Brahmanism

is rejected, including the most typical dogma of all, the worship of caste.The

sect owes its origin to Guru Nanak Shah, who preached this reformation towards

the end of fifteenth century. Their rulers, who eventually combined the functions

of military chief and spiritual leader, were called Gurus (Teachers) of whom the

tenth was the last.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Sikhs formed

themselves into Misls (Confederacies), each (Misl functioning) under control of

a Sardar (or Chief)- These confederacies practically controlled the whole of Panjab.

But some hundred years

later all these Confederacies fell under the rule of

the famous Ranjit Singh, who died in 1839.-

After (Maharaja Ranjit Singh's)

death, a rapid succession of weak and incompetent rulers followed, accompanied

with much disorder, intrigue and considerable fighting between different faction

and parties.

The Sikh army now guided by its own self-elected Military Councils

became a law unto itself, and believing itself invincible determined on attacking

the British, driving them out of their northern possessions, and capturing and

plundering Delhi, against the old Muhammedan King (Bahadur Shah Zafar) and people

whom they owed a deep and dead religious enmity.

In December 1845, the Sikh

army crossed the Satluj, and commenced the hard fought Satluj Campaign. Finally,

the British victory at Sabraon in 1846, followed by that of Gujrat in 1849 resulted

in the (British) annexation of the Panjab.

Amritsar is a comparatively modem

city, having been founded in 1574 by Guru Ram Das. The chief attraction is the

famous Golden Temple built by (Guru) Ram Das (Guru Arjan -editor.) in the middle

of the lake (variously known as (Amritsar, Amritsarovar, Sudhasar and Sudhasarovar

term meaning) the Pool of Immortality."

Perhaps no temple in India possesses

so striking and beautiful a situation as this remarkable and sacred temple of

the Sikhs. In the dazzling sunshine, this beautiful sanctuary, with its burnished

copper gilt roof, shines like gold, while the lake is bordered with palaces of

wealthy Sikh chieftains with a background of shady groves gardens. From the mass

of greenery stand out, white and dazzling, soaring minarets, pinnacles and towers,

while the many coloured throngs of pilgrims on the terraces of the lake and the

marble causeway enliven the scene. The temple is reached by an arched causeway

inlaid with cornelians, agates and other stones. The Golden Temple stands on a

platform in the middle of the lake: it is a small building, and not of the slightest

architectural merit, but owing to the richness of its decoration and the unique

charm surroundings, it is (part of) one of the most attractive (complexes) in

India.

In the Temple sits the Chief Priest surrounded by a large number of

white robed priests, who sit round a large silken sheet piled with roses. The

Chief Priest chants a verse from the Granth, the Sikh Bible. The other priests,

musicians and devotees chant the alternative verses, while all the worshippers

file slowly past the Chief Priest in a reverent manner, sing and throw into the

silken sheet roses and other flowers as well as money from the smallest copper

to silver and gold pieces and occasionally jewellery. The whole ceremony is so

simple yet impressive that a visitor leaves the Golden Temple with a feeling that

he has not been looking at a sight, but at a reverent act of worship.

Another view of the Temple in the 19/20th centuries

The present Grandeur of the Golden Temple or Harimandir Sahib

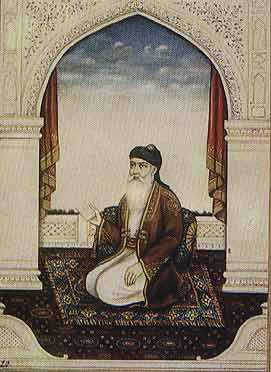

MAHARAJA RANJIT SINGH

In the respectable virtues, he had no part, but in their default he was still great. He was great because he possessed, in an extraordinary degree, the qualities without which the highest success cannot be attained. ... To the highest courage he added a perseverance which no obstacles could exhaust, and he did not fail in his undertakings, because he never admitted the possibility of failure.

Maharaja

Ranjit Singh was born in 1780. At the age of eleven, on the death of his father

Sardar Mahan Singh, Ranjit Singh became the nominal chief of the Sukarchakia Misl.

When sixteen, he killed his mother for infidelity to the memory of his father.

In

1797, at the age of seventeen, he assumed the leadership of Sukarchakia Misl,

and soon showed his military qualification and great aptitude for command by leading

his men, first against his Muhammedan neighbours, and afterwards, as his followers

increased, against some of the weaker Sikh Misls.

When Shah Zaman of Kabul

invaded the Panjab for the last time, he appointed Ranjit Singh, in 1799, as the

Governor of Lahore. (Maharaja Ranjit Singh had captured Lahore on 7th July 1799,

therefore the 'appointment' by Shah Zaman is wrong - Ed,) Ranjit Singh soon firmly

established his authority in that city and its neighbourhood: and in 1801, having

assumed the title of Maharaja, proceeded by force and craft gradually to subdue

the Sikh Misls north of Satluj. By degrees, he extended his rule all over the

Panjab, and the Himalayan Mountains bordering it, including Kashmir and Ladakh,

as well as to the foot of the mountains on the Afghan border.

Ranjit Singh's

reign was a long campaign in consolidating his power of which it is impossible

to give any account here.

Ranjit Singh was a far-seeing man who never wavered

in his loyalty to the Treaty he made with the British Government, well comprehending

its great power, and fully trusting that as long as he abided by the terms of

the Treaty, the British Government would also do so and would not interfere with

him.

Although short of stature and disfigured by smallpox by the loss of one

eye, Ranjit Singh was an ideal soldier, strong, aware, active, courageous and

enduring, an excellent horseman, keen sportsman and an accomplished swordsman.

He

was quite uneducated, could neither read nor write, but had a marvellous memory.

Ranjit

Singh had an unusually large share of the weaknesses and vices in human nature.

Ranjit

Singh was selfish, false and avaricious; grossly superstitious, shamelessly and

openly drunken and debauched.

In the respectable virtues, he had no part, but

in their default he was still great. He was great because he possessed, in an

extraordinary degree, the qualities, without which the highest success cannot

be attained.

Ranjit Singh was a born ruler with the natural genius of command:

men obeyed him by instinct because they had no power to disobey him.

To the

highest courage he added a perseverance which no obstacles could exhaust, and

he did not fail in his undertakings, because he never admitted the possibility

of failure.

He possessed the faculty of choosing his subordinates well and

wisely, and consequently he was, in a corrupt and violent age, wonderfully well

served.

His natural avarice and rapacity were tempered by his appreciation

of the advantages of generosity in rewarding good services. With all his rapacity,

Ranjit Singh was not cruel or bloodthirsty, and after a victory or capture of

a fortress he treated the vanquished with leniency and kindness. To cite an instance

of his rapacity, by means of most unscrupulous methods, he compelled the fugitive

King of Kabul Shah Shuja, then his guest at Lahore, to give to him the celebrated

Koh-i-Nur diamond.

Although sharing in full the course vices of his time, he

yet ruled the country, which his military genius had conquered with a vigour of

will and ability, in such way as placed him in the first rank of the statesmen

of the century.

The six years, which followed Ranjit Singh's death in 1839,

were a period of storm and anarchy, in which assassination was the rule and the

weak were trampled under foot.

The Kingdom founded in violence, treachery and

blood did not long survive its founder. Created by the military and administrative

genius of one man, it crumpled into powder when the spirit, which had given it

life, was withdrawn.

The death of Ranjit Singh, in fact, was followed by a

series of crimes and tragedies such as had rarely paralleled in history, save

in the darkest days of downfall of Rome, or in the early days of the French Revolution.

At

Ranjit Singh's funeral obsequies, one of his wives and three ladies of his zenana

of the rank of Rani were burnt with him.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh married eighteen

wives, nine by the orthodox ceremonial, and nine by the simpler rite of throwing

the sheet. The Maharaja had many reputed sons, but only one legitimate one, Kharak

Singh, who succeeded him.

COMMENTS

In

his work 'Ranjit Singh' Khushwant Singh quotes Lieutenant Bennett's English translation

of Shah Shuja's autobiography containing the deposed Afghan King's personal evidence

to the effect that privation of necessaries of life, occasional placement of Lahore

Durbar guards around his abode and interdiction on his visiting his zenana comprised

the measures resorted to by Ranjit Singh to coerce him to part with Koh-i-Nur.

Cf.

A. S. Baaghaa's Panjabi work Mahabali Ranjeet Singh:

On 27th June 1839, the

crest-fallen Ranjit Singh lay on bed. Bhai Gobind Ram whispered into his ears:

"O bread-giver, pronounce Ram, Ram, Ram." Ranjit Singh's lips moved

twice. A third effort to invoke Ram bore no fruit. The swan fluttered away from

the elemental cage. Dolorous shrieks arose from zenana. The Maharanis pulled their

hair and beat their heads on walls. The sun sank down the western horizon. Despondency

lurked in the air. Sikh hymnists hummed verses of Guru Granth: Brahmans, on their

part, pronounced Gita's text. On 28th June 1839, Kharak Singh put on dhoti round

his waist and poured gangajal on his dead father. Ranjit Singh's spouse Hardevi

reminded Vizier Dhian Singh of his pledge that he would accompany his master in

his journey to the next world. Clad in new garments, Dhian Singh ran to his master's

pyre. Kharak Singh put his turban.

on Dhian Singh's feet and said: "Please

do not die, because at this distressful hour, we have none else who can steer

ashore the governmental barge."

While Maharani Gaddan walked to her dead

husband's pyre, she begged Dhian Singh to stand by Kharak Singh for a year. She

told him that thereafter he would be at liberty to itinerate to holy places. Gaddan

sat in the centre of the pyre. She placed Ranjit Singh's head on her thighs. Gaddan,

Hardevi and two more Maharanis formed the inner ring of Satis. Seven handmaids

sat behind them on the pyre. Maharani Gaddan placed Dhian Singh's hand on Ranjit

Singh's breast. "Remain faithful to Kharak Singh," she said. She spoke

out to Kharak Singh: "Abide by Dhian Singh's counsel." Kharak Singh

set the pyre aflame. Maulvi Ahmad Bakhsh Chishti' Yakdil' reports that at that

time the clouds sent down soft shower as send-off to the fairies who burnt on

pyre. Two pigeons descended from sky and joined the dead Maharaja's partners in

their fervent homage to the Lion of Panjab.

Fourteen creatures comprising one

man, eleven women and two pigeons were together consumed by tongues of fire, which

arose heavenward. McQueen wrongfully reduces the self-immolators to a mere pentad.

Waheeduddin,

op. cit., basing his information on heirloom record, makes no secret of it that

Ranjit Singh's exploits on bed involved as many as forty-six women comprising

regular wives, widows, handmaids and concubines.

In his work, A History of

the Sikh People, Gopal Singh observes that the British writers perhaps conspiratorially

denigrated Ranjit Singh's sons as illegitimate and that some modern Hindu and

Sikh scribes followed suit. Jagjiwan Mohan Walia quotes Foreign Consultations

Record preserved in National Archives of India while he observes in his work,

Parties and Politics at Sikh Court: 1799-1849, that in 1827 Kharak Singh wrote

a letter to the Governor of Bombay Mountsruart Elphinstone, soliciting British

government support against Prince Sher Singh in his candidature for inheriting

Maharaja Ranjit Singh's power and pelf. Jagjiwan Mohan Walia affirms that in the

aforesaid letter Kharak Singh declared that Sher Singh and Tara Singh were not

real sons of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The letter was signed by Kharak Singh's son

Nau Nihal Singh also. Thus the scandalous infamy of Ranjit Singh's sons sprouted

from the ambitious rivalry of Kharak Singh and Sher Singh each of whom wanted

to steal march on other to seize Lahore throne. Each got the coveted lofty status

only to lose the same in miserable premature demise.

Towards the end of 1826,

Maharaja Ranjit Singh became seriously ill. Of course, the matter of his father's

recovery was of no higher concern to Kharak Singh than his own installation as

the Ruler of Lahore in the event of his father's malady assuming mortal proportions.

This explains the background of the aforesaid correspondence addressed by Kharak

Singh to Elphinstone in regard to the formers pre-emptive claim to sovereign monarchy

of Lahore on the ground of his supposed

half-brothers Sher Singh and Tara Singh

having not been born in lawful wedlock.

The pure mind scans merit rather than

birth as the succession criterion. Guru Nanak chose his devotee Angad as his successor

because the latter rather than the formers sons mirrored the

The psyche and

ethos of Guru Nanak. Literally, the term Angad means one born of limb' i.e. son.

In Guru Nanak's logic, the son is born of the father's spirit rather than his

physical frame.

The ideal son would not clamour for patrimony: nor does ideal

dad deny privileges to the dutiful son.

Unfortunately, the reigning family

of Lahore failed to imbibe the principles of Guru Nanak. The inevitable result

was that they indulged in internecine spite and ruined themselves.

MAHARANI JINDAN

Maharani

Jindan, the mother of Dalip Singh, was the daughter of a common trooper in the

service of Ranjit Singh.'

Jindan attracted the attention of the old Maharaja,

as a clever mimic and dancer, and was taken into his zenana, where her open intrigues

caused astonishment in the Court of Lahore.

A menial servant, Gullu, a water-carrier,

was generally accepted as the father of Dalip Singh: at any rate, the father was

not Ranjit Singh who was paralysed several years before the birth of the child

nor did he ever marry Jindan by formal or informal marriage.

In the wild anarchy

which succeeded the murder of Maharaja Sher Singh, Jindan, with her last professed

lover, Raja Lal Singh played a conspicuous and infamous part, and they both were

in a great measure the cause of the Satluj War, and the ruin of the Sikh Kingdom.

In

1848, before the annexation of the Panjab, Jindan banished to Hindustan, on account

of the prominent part she took in a conspiracy against the British Resident. She

was eventually allowed to go to England, where her son Dalip Singh had been provided

with a home.

Jindan died in England in 1863, aged 46.

COMMENTS

Jindan was born in 1817 in a village about three miles to southwest of Gujranwala

in present Pakistan. Her father named Manna Singh Aulakh was actually Maharaja

Ranjit Singh's kennel-keeper, later raised as chamberlain.

Manna Singh Aulakh was a humorist in Lahore Durbar. When Jindan was eleven years

old, Aulakh, waggishly and suppliantly, suggested to Maharaja Ranjit Singh that

he wondered whether his darling daughter would in due course blossom into an exuberant

decoration-piece worthy of adorning that mighty monarch's bedchamber.

Jindan

dextrously developed her innate potential for growing into an adept nautch-girl.

Her voluptuous exterior made her the focus of many a longing eye.

We learn

from Memoirs of Alexander Gardner, that Ranjit Singh took Jindan into his harem

where the little beauty used to gambol, and frolic and tease and captivated the

Maharaja in a way that smote the real wives with jealousy. In 1830, with the object

of calming the jealousy of his wives, the Maharaja sent Jindan, then thirteen,

to her godfather at Amritsar where her amorous glances and coquettish pranks continued

attracting lustful attentions of no small number of erotic truants.

At long

last, Jindan's godfather begged of Maharaja Ranjit Singh the permission for escorting

the wayward damsel back to Lahore.

Contrary to Sir John McQueen's observation

that Ranjit Singh never married Jindan formally or informal ly, the work Flashman

and the Mountain of Light, based on The Flashman Papers 1845-1846, and edited

and arranged by George MacDonald Fraser, affirms that in 1835 Jindan went through

a form of marriage with Ranjit Singh.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh had first paralytic

attack in July 1835. In December 1838, amid festive entertainment of the British

Governor-General of India, Lord Auckland, during the latter's visit to Lahore,

the Maharaja was gripped by a second paralytic attack.

The Flashman s Papers

referred to above suggest that Jindan's exuberant charms possibly turned the smouldering

sexual ash within Ranjit Singh into a virile storm and that on this count Dalip

Singh was probably a legitimate son of the Lion of Panjab.

The motive of the conspiracy alluded to by McQueen was the murder of the British

Resident at Lahore Lt. Col. Hen Lawrence and his henchmen. The plan, which had

the secret, and hence non-provable sanction of Jindan, aborted because of its

unfortunate leakage. In August 1847, Maharani Jindan was removed to Shekhupura

Fort. In May 1848, accompanied by pro-British hostile escort she left that fort,

crossed the Satluj to Firozpur and moved to Banaras Fort to rot in confinement.

In April 1849 she was taken to Chunar Fort. From there Jindan escaped out in the

guise of a seamstress. After that her journey in the false appearance of a Bairagan

terminated on her entry in Nepal where her request for asylum elicited a warm

response. There she lived in Khatmandu on the bank of the Rill known as Vegmati

while scenes of lost glory recurrently flashed on her inner screen. Towards the

end of 1860, Dalip Singh specially journeyed to India to bring his mother to England.

Dalip Singh's erstwhile Tutor and Guardian, Sir John Login, secured a house for

Maharani Jindan on Lancaster Gate in London. Login himself lived in the house

then called No. 1 Round-the-Corner. This was only one house between Login's residence

and the house procured by him for Jindan. In mid-1862, Jindan occupied Abingdon

House in Kensington in London where she lived till death. In this connection,

the work entitled 'The Tablet', dated back to 10th April 1875, and preserved in

London's Colindale Library provides the following information on its page 454:

...

the mansion was occupied by the widow of a ce-devant Indian potentate of high

rank, with her Hindoo servants and retainers. A local rumour, which we are unable

to confirm or contradict, says that during the residence of the Ranee at Abingdon

House, it was the scene of Hindoo religious ceremonies, and even of sacrifices,

that were practised by the inmates. It this was really the case, the lustration

which the house and grounds must have undergone, it being now devoted to Christian

uses, must have sufficiently purged away all taints of diabolic fraud and pagan

superstition.

The publication Survey of London, Volume XLll, Greater lLondon Council, 1986 refers to The Tablet, reproduces a partof its above extract and adds that in 1720 the site of Abingdon House was acquired by Sir Isaac Newton, that in c. 1838 a tenant of some standing, named the Fourteenth Lord Teynham resided there, that in 1861-62 Mamaduke Wyvill, M.P., was tenant in it and that at one stage, perhaps after Wyvill, the house was occupied by the widow of a ce-divant Indian potentate.

The exact date of Jindan's death is 1st August 1863. George MacDonald Fraser is wrong while he observes op. cit. p. 370 that Dalip Singh took his mother's ashes to India: he took her dead body to India, not her ashes. After Jindan's death, her dead body was stored in a vault in Kensal Green Cemetery in London. In mid-February 1864, the body was exhumed for taking it to India. There it was cremated at Nasik whereafter the ashes were scattered on the waters of Godavri. After her banishment from Panjab, Jindan, alive or dead, was denied return to Punjab.

McQueen s account omits some quite important events. He does not notice that on Dalip Singh's coronation in September 1843, Jindan and her brother Jawahar Singh arose as Joint Regents to him. Nor does he mention Jindan's dismissal as Regent towards the end of 1846.

MAHARAJA KHARAK SINGH

Kharak Singh, the only legitimate son of Ranjit Singh, succeeded his father as Maharaja in 1839.

Under the influence of Sardar Chet Singh, a court favourite, the late (Maharaja Ranjit Singh's) Minister, Raja Dhian Singh, was ignored and insulted, and a plan made to assassinate him. But this coming to the Minister's knowledge, he resolutely formed a Coalition with some Chiefs and Maharaja Kharak Singh's only son, a capable youth of fiery and ambitious temper. They circulated a rumour that Kharak Singh contemplated submission to the British Government when the Sikh army would be disbanded. This powerfully appealed to the soldiery, who consequently looked upon the Maharaja as a traitor to his country.

The Minister, with his adherents, entered the palace before sunrise, cut down the Royal Guards, penetrated to the private apartments and killed the obnoxious favourite (Chet Singh) in the presence of his Master (Kharak Singh).

After a reign of three months, Kharak Singh was deposed, and his son Prince Nau Nihal Singh placed on the throne.

The deposed Maharaja died the following

year, not without suspicion of poisoning, and his son (Nau Nihal Singh), while

returning from his father's obsequies, mysteriously met his death by what is called

an accident.

The designing Minister Raja Dhian Singh now outwardly supported

the claim of the Queen Mother Chand Kaur to govern as Regent (to the child which

late Nau Nihal Singh's pregnant widow would deliver), but secretly he inspired

Prince Sher Singh advance his claim to throne as a reputed and acknowledged son

of Ranjit Singh.

COMMENTS

In conformity with Maharaja Ranjit Singh's wish, Kharak Singh was anointed as his successor on 21 st June 1839 six days before the formers death.

Chet Singh was a Bajwa Jat. He was a close relative of Kharak Singh's brother-in-law Mangal Singh Sandhu. While he was obstinate, fastidious, avaricious and arrogant, he was much less shrewd and much less wily than Raja Dhian Singh whom he wished to supersede through sycophantic and panegyric acting before Kharak Singh. Bajwa oft resorted to boastful threats as means to cow down his rival Dhian Singh.

On 8th October 1839, during night Dhian Singh and his adherents, namely, his two brothers Gulab Singh and Suchet Singh, Prince Nau Nihal Singh whose counsel his father Kharak Singh had, of late, been apathetically disparaging, Treasurer Lal Singh, Col. Alexander Gardner, Suchet Singh's Adviser Rai Kesri Singh and the leading Sandhanwalia Sardars entered the royal palace for soiling their hands with the blood of Bajwa whose influence on the mentally retarded Kharak Singh was foiling every attempt of Prince Nau Nihal Singh to retract him from fallacious policy.

As yet Nau Nihal Singh was at the most a self-appointed Regent and by no means a de jure Maharaja. In native accounts his name is invariably prefixed by Kanwar i.e. Prince.

Kharak Singh died on

5th November 1840. While Nau Nihal Singh and Gulab Singh's son Udham Singh walked

back together after the antam ardas or last prayer at the cremation of dead body

of Kharak Singh, the archway under which they walked gave way. The impinge of

stones which pelted down killed Udham Singh on the spot and wounded Prince Nau

Nihal Singh above his right ear. The Prince staggered down, made an effort to

rise and demanded water. Nau Nihal Singh was carried into the palace. In vain

the Prince's sad and furious mother beat the fort gateway which Dhian Singh kept

shut on Nau Nihal Singh's kith and kin.

The contemporaneous evidence preserved

in Memoirs of Alexander Gardner and in Dr. J. M. Honigberger's Thirty-Five Years

in the East, H. Bailliere, London, leads us to conclude that what the collapse

of archway failed to attain was achieved by Dhian Singh's recourse to homicide.

The Kanwar met death while on way to investiture as Maharaja! None demanded or

ordered enquiry into the grievous tragedy. Dhian Singh's uncharitable refusal

to admit Nau Nihal Singh's mother Chand Kaur to the palace to enable her to tend

her wounded son is in itself an adequate evidence of his sinister motive. At the

same time Chand Kaur's failure to storm the gate to gain access to her son proves

her utter resourcelessness.

MAHARANI CHAND KAUR

Chand

Kaur, daughter of Sardar Jaimal Singh Kanhaiya of Fatehgarh near Gurdaspur, married

Maharaja (then Kanwar or Prince) Kharak Singh in 1812. The marriage was celebrated

with great splendour, and General (Sir David) Ochterlony attended the ceremony.

In

1821 Maharani Chand Kaur gave birth to her son Nau Nihal Singh.

On the deaths

of her husband Kharak Singh and her son Nau Nihal Singh, both on 5th November

1840, Chand Kaur laid claim to Sikh crown.

Chand Kaur's claim was supported

by the powerful Sandhanwalia Sardars, and also by, as she thought, Raja Dhian

Singh, the Prime Minister, who was, however, only deceiving her, as he was actually

working at that time on behalf of Prince Sher Singh.

The Minister's elder brother

Raja Gulab Singh, with his troops fought for Chand Kaur, and held the Fortress

of Lahore against Prince Sher Singh and the Sikh army during five days' hard fighting.

[On

its surrender (i.e. surrender of Fortress) Chand Kaur renounced her claim to the

Sikh throne.

The Dogra brothers. Rajas Gulab Singh and Dhian Singh Apparently

often espoused opposite sides, but they were secretly forking in unison, for their

armies were common. (Their inner motive was advancement of themselves and their

kindred to wealth and power, at all hazards)

In 1842 Maharani Chand Kaur was

murdered by her own slave girls to whom she had been inordinately cruel. They

beat her to death with their own slippers. Dhian Singh and Sher Singh are believed

to have instigated the slave girls, by giving them money and promising them further

rewards, to kill their mistress, whom it was well known they hated.

The slave

girls were, however, made prisoners. The hands of two of them were cut off. One

was released in consideration of her giving a large sum of money as the ransom

of her life. The fourth, however, managed to effect her escape.

Prince Sher

Singh had at one time wished to marry Chand Kaur, principally for political reasons

and her great wealth, but she had rejected his proposals with disdain. His enmity

was further greatly aroused against her by Dhian Singh telling him that Chand

Kaur had declared that he (i.e. Sher Singh) was either a fool or a madman to suppose

that she, the daughter of the great Jaimal Singh of the famous House of Kanhaiyas,

would ever think of allying herself with him, the son of a washerman.

This

last allusion was to the fact that Maharani Mehtab Kaur, one of Ranjit Singh's

wives, and the reputed mother of Sher Singh had never had any children, but had

purchased two boys, one of them Sher Singh from poor parents, and had passed them

off as twins she had borne Ranjit Singh, hoping thereby to retain her influence

over the great Maharaja.

COMMENTS

Through

the mediation of Dhian Singh, Gulab Singh extracted a word from Sher Singh that

in the event of evacuation of the stronghold, his army would take away with impunity

the personal effects of Chand Kaur entrusted in his custody. In The Founding of

Kashmir State, Alien & Unwin, London, 1953, K. M. Panikkar bears out that

a convoy of sixteen bullock-carts carrying silver and gold coins and five hundred

horses each laden with a bagful of sovereigns emerged out of the Lahore Citadel

and headed for Jammu. With this wherewithal Gulab Singh later purchased Kashmir

from the British. Verily it was a colossal pilferage of Royal Treasury.

Chand

Kaur expired in June 1842. The trio of the accomplices in the plot, which consummated

in her death, comprised Dhian Singh, Gulab Singh and Sher Singh. Hungry hyenas

lurk and vicious vermin crawl, while godmen watch and wonder. But Chand Kaur had

little virtue on her part to place her above Sher Singh. She had a large share

of arrogance. She was peevish and snobbish. She had appended a tall title to her

name. She called herself Malika Muqaddas or Pious Queen.

MAHARAJA NAUNIHAL SINGH

Nau

Nihal Singh, the son of Maharaja Kharak Singh was a handsome, vicious and ambitious

youth, who was entirely guided by the crafty Minister Raja Dhian Singh.

On

the deposition and imprisonment of his father, Nau Nihal Singh was proclaimed

Maharaja.

Nau Nihal Singh seldom saw his imprisoned father, but when he did

so, it was only to threaten and abuse him.

When his father's death was announced

to him, instead of being affected by it, he seemed to think that now the day of

his rejoicing and happiness had arrived and calmly gave orders for the cremation

of his father's corpse.

This ceremony was performed in an open space opposite

the mausoleum of Ranjit Singh. On its completion Nau Nihal Singh, taking the hand

of Mian Uttam Singh, son of Raja Gulab Singh and nephew of the Minister Raja Dhian

Singh, started at the head of the returning funeral procession to proceed through

a deep arched gateway.

As they were emerging from the gateway, a crash was

heard: beams, stones and tiles fell from above, and the two young men were struck

to the ground.

Mian Uttam Singh was killed on the spot, but the young Maharaja

was picked up senseless, placed on a litter and conveyed to an apartment in the

adjacent Lahore Fort by Dhian Singh, who allowed no one to see or attend upon

him except himself and two of his immediate followers. Then it was that the infamous

Dhian Singh had him smothered: at least the Sikhs and others came to think so.

At

first it was given out to the Sikh Sardars, that Nau Nihal Singh was likely to

do well, was only wounded and for a time insensible.

Shortly afterwards Dhian

Singh visited Nau Nihal Singh's mother, and told her that her son had died about

half an hour after his removal to the Fort.

Dhian Singh then convened an Assembly

of some of the principal Sikh chiefs and told them the same story, and advised

that the Maharaja's death should not be made public fora few days, when it should

be decided whether Nau Nihal Singh's mother Maharani Chand Kaur, or Prince Sher

Singh, a reputed son of Ranjit Singh, should be selected to rule.

Dhian Singh

had promised Chand Kaur during his interview with her that she should reign, but

his great object was to ensure her silence and gain time, until the arrival of

Sher Singh to whom he had privately written to lose no time in coming to Lahore.

On

Sher Singh's arrival the death of Maharaja Nau Nihal Singh was publicly made known,

and after much intriguing and some very severe fighting Raja Gulab Singh, who

was supporting Chand Kaur's claim and maintaining the Citadel of Lahore against

the Sikh army, surrendered the Citadel to Sher Singh, who became the Maharaja

of Panjab.

COMMENTS

As

observed in Maharaja Kharak Singh- during the period from de facto deposition

of Kharak Singh to his death, Nau Nihal Singh may be more correctly designated

as a self-appointed Regent rather than a full-fledged Maharaja.

The real name

of Gulab Singh's son who was mortally struck under impact of crashed masonry was

Udham Singh.

MAHARAJA SHER SINGH

Within

eighteen hours of murderous assaults on Maharaja Sher Singh. his twelve-year-old

son Partap Singh and Vizier Dhian Singh, the Sikh soldiery killed the killers.

When

Maharani Mahtab Kaur had been married to Ranjit Singh for more than ten years

without bearing him any children, it was given out soon after Ranjit Singh's departure

from Lahore on his cis-Satluj campaign of 1807 that the Maharani was pregnant.

On

the Maharaja's return, his wife presented him with Sher Singh and Tara Singh as

her twin sons.

But Ranjit Singh was not deceived: he knew his wife was barren

and had bought the children to pass them off as his own, and had once before for

the same purpose purchased one which had died. It, however, suited him to acknowledge

these children as his own, and they were always treated as his sons and bore the

title of Shahzada (meaning) Prince.

Sher Singh succeeded Nau Nihal Singh in

1841.

Sher Singh was a brave but stupid man, had seen much service with the

Sikh army and was popular with the soldiers, with whose aid he was subsequently

able to establish himself on the Sikh throne, after compelling Raja Gulab Singh

to surrender the Citadel o Lahore.

Shortly after the succession of Sher Singh

intrigues and a most mutinous spirit became rampant in the Sikh army, and the

Maharaja and his Government soon lost all control over it.

The military administration

was conducted by Panchayats of Councils of five delegates per Regiment elected

by their comrades, who demanded increase of pay, dismissal of all officers obnoxious

to them etc. On their demands being refused they murdered many officers, and plundered

Lahore. At last, tired of their own excesses, they modified their requests and

tranquillity was restored, but discipline and subordination in the army had entirely

ceased.

Maharaja Sher Singh, on all occasions, expressed himself favourable

to the British, scrupulously adhering to Ranjit Singh's policy regarding them.

It was solely owing to him, that the British army, returning from Afghanistan

in 1842, was allowed undisputed passage through Panjab, though many of the Sikh

chiefs were anxious to attack it, as they thought that the potent spell of victory,

so long attached to the British arms had been broken at Kabul, and by the policy

of evacuating Afghanistan.

About two years after Sher Singh's accession, he

was assassinated on 15 September 1843 by the Sandhanwalia Sardars Ajit Singh and

his Uncle Lehna Singh.

Immediately after the completion of the foul murder,

they with their followers proceeded towards Lahore three miles distant.

On

their way they met Raja Dhian Singh, who had instigated them to kill Sher Singh.

They, having killed the Maharaja, insisted on Raja's going back to his house (and

pretended that there) they wished to tell him (in detail) what had occurred, and

(that there they wanted) to consult him as to what steps should now be taken (to

consolidate gains to mutual advantage).

As the Sandhanwalia Sardars and their

followers far outnumbered the few men with Dhian Singh, he was forced to comply,

but no sooner had they dismounted at his house and gone inside with him than they

murdered him and some of his followers.

Dhian Singh's son Raja Hira Singh,

having escaped when his father was killed, rode at once to the large Sikh (army)

camp in the neighbourhood of Lahore, made a stirring speech to the soldiers, telling

them of the murders of their Maharaja, and of his father Dhian Singh by the Sandhanwalia

Sardars Ajit Singh and Lehna Singh, whom he declared traitors (to the Lahore Durbar)

and friends

of the British. He also said that their pay would be increased,

and that he would moreover reward them with largesse from his own and his father's

funds.

The soldiery at once responded to Hira Singh's speech, marched on Lahore

Fort, stormed and took it that evening, killing Sardars Ajit Singh and Lehna Singh

and exterminating their followers. Thus within eighteen hours these men met the

just punishment for crimes they had committed that day.

COMMENTS

Sher

Singh's service with Sikh army alluded to by Sir John W. McQueen included his

occupation of Jahangiria Fort, dislodging the Barakzai half-brothers Dost Muhammad

Khan and Jabbar Khan from their entrenched positions near that fort, inflicting

severe defeat on the Muslim fanatic Sayyad Ahmad Barelvi in 1829, snatching from

him Peshawar and exhorting the Sikh army to despatch him in the jaws of death

in the engagement fought in May 1831 at Balakot in Hazara area.

The British

diplomat Alexander Burnes was murdered in Kabul on 2nd November 1841.

After

that event, Dost Muhammad Khan's son Akbar Khan slaughtered Governor-General Lord

Auckland's Political Adviser Sir William Macnaghten while both were in conference.

The Treaty of Evacuation was signed on 2nd January 1842. Four days later, British

soldiery 16,000 strong budged away from the camping grounds. Out of them Dr. Brydon

alone reached Jalalabad to narrate the vicissitudes of the journey. Subsequent

events included Shah Shuja's murder by his nephew in April 1842, Akbar Khans'

reverses in two battles with General Pollock, the fall of Ghazni, the British

capture of Kabul on 16th September 1842, the British bombardment of Kabul Bazar

as the only resort to conceal British plight, evacuation of Kabul on 12th October

1842 and retirement of British army via Khyber Pass.

In his poetic work Vijay

Vinod in mixed Hindi-Panjabi-Urdu authored in 1844 and published by Shiromani

Gurdwara

Prabandhak Committee, Amritsar in 1950 as part of Prachin Jangname,

ed. Shamsher Singh Ashok, Gwal reports that in the Baradari (near) Shah Bilawal,

(three miles from suburbs of Lahore), Sardar Ajit Singh Sandhanwalia told Maharaja

Sher Singh that he had secured a London-made double-barrelled firearm. When Maharaja

Sher Singh advanced his hand to receive the weapon, Ajit Singh Sandhanwalia pressed

its trigger while his soldier standing behind him beheaded the Maharaja. To the

foregoing Gwal's version Pandit Debi Prasad adds in his Urdu work Tarikh-i-Panjab,

Bareli, 1850 that Ajit Singh laughed while in loud voice he told Maharaja Sher

Singh ensconced in chair reclining on cushion: "This double-barrelled (rifle)

has been purchased for fourteen hundred (rupees), but I shall sell it not even

for three thousand (rupees)."

In the meanwhile, (in the nearby Tej Singh's

Garden), Lehna Singh Sandhanwalia killed (Maharaja Sher Singh's twelve-year-old

son) Prince Partap Singh.

Gwal, op cit., records that Ajit Singh Sandhanwalia

endeavoured to descend from the fort but the rope held by him snapped. While he

fell on ground, the sepoys rushed on him and chopped his head. Gwal further reports

that the trunks of the dead Lehna Singh and Ajit Singh were hung in Lahore respectively

on Masti Gate and Dilli Gate.

MAHARAJA DALIP SINGH

He was without any force of character, vain and weak, liked society and being noticed and made much of, entertained largely and was famous for his shooting parties.

After

the Satluj Campaign, when the British army reached Lahore in March 1846, Dalip

Singh, a child of nine years, was the titular Maharaja of the Panjab, and as it

was convenient to accept the status quo and a Ruler being required for the country,

which the British Government had then no desire to annex or permanently occupy,

the reputed child of Maharani Jindan and the water-carrier Gullu was confirmed

on the throne of the Lion of Panjab.

Fortune, with her ever turning wheel,

must have laughed at the transformation.

After the general outbreak of the

Sikhs in 1848 all over the Panjab, which led to Second Sikh War, Dalip Singh was

deposed on 29th March 1849, and sent to Fatehgarh in Hindustan, and subsequently

in 1851 to England.

Dalip Singh was well educated, and brought up as an English

gentleman, moved in the best society in town and country, was provided with a

large, fine Estate, and Mansion in Norfolk, and had a liberal income granted him

by the Government of India.'

Dalip Singh was without any force of character,

vain and weak, liked society and being no'iced and made much of, entertained largely

and was famous for his shooting parties. He interested himself in his Norfolk

Estate, and was very particular in preserving game. Also Dalip Singh rented for

many years some excellent grouse moors in Scotland. He was a most keen sportsman

and a first class shot.

Dalip Singh was very extravagant, and though the Government

of India once came to his assistance, he thought it would continue to do so, and

so made no attempt towards reducing his expenditure.

In 1861, Dalip Singh went

to India for a few months with the hope that his presence in that country might

move Government to give him a large income or a lumpsum to pay his debts, but

this plan had no immediate result.

In 1864 Dalip Singh married an Abyssinian

lady by whom he had a son Prince Victor Dalip Singh, who on his father's death,

succeeded to what was left of Maharaja Dalip Singh's property, but not to his

title.

Maharaja Dalip Singh died in 1890.

COMMENTS

In

his Panjabi work Mahan Kosh, Bhai Kahan Singh writes that Maharaja Dalip Singh

was born in February 1837, but he points out that some writers give the Maharaja's

date of birth as 4th September 1838. The author of the Parties and Politics at

the Sikh Court: 1799-1849, reports on page 127 of that work that Dalip Singh was

born in 1838. The author of The Khalsa Raj, New Delhi, 1985 observes on pages

183 and 184 of that work that following the murders of Maharaja Sher Singh and

his son Partap Singh on 15th September 1843, the five-year-old son of the late

Maharaja Ranjit Singh was raised to the throne.Thus Dalip Singh was five years

old in September 1843 whence we conclude that he was born in September 1838.

Maharaja

Dalip Singh's journey to Fatehgarh in present Uttar Pardesh in India commenced

in April 1849. He sailed for England on 19th April 1854.

Based on the information

supplied by Dalip Singh himself, an Editorial of Moscow Gazette published in September

1887 revealed that Dalip Singh was treacherously deprived of his Kingdom and was

not permitted to receive education at Cambridge or Oxford lest his innate genius

should develop and grow.

Dalip Singh's Abyssinian wife Bamba Muller bore him

three sons Victor Dalip Singh, Frederick Dalip Singh and Albert Edward Dalip Singh,

respectively born in 1866,1868 and 1879. The couple had three daughters Bamba

Jindan, Katherine and Sophia Alexandra born respectively, in 1869, 1871 and 1874.

Bamba Muller passed away on 18th September 1887. On 21st May 1889, in Paris, Dalip

Singh married A. D. Wetherill. Dalip Singh's children died issueless.

Maharaja

Dalip Singh died as a paralytic patient like his real or supposed father Ranjit

Singh. On 22nd 1893, in his apartment in Grand Hotel in Paris he encountered death

while lost in slumber. His dead body was removed to England to be buried in the

church graveyard in his estate in Suffolk. There he rests in the grave while the

Sikh simpletons continue visiting it and calling it Samadh. Grave is translatable

in Panjabi as Qabar, not as Samadh. Samadh is a monument erected in memory of

a deceased Hindu or Sikh saint, warrior, martyr or potentate.

RAJA GULAB SINGH

There are perhaps no characters in Panjab History more repulsive than Rajas Gulab Singh and Dhian Singh: their splendid talents and undoubted bravery only rendered more conspicuous their immorality, atrocious cruelty, treachery, avarice and unscrupulous ambition.

Sometime previous to his death,

Ranjit Singh had taken into special favour his Prime Minister Dhian Singh's family

consisting of his two brothers Gulab Singh and Suchet Singh and his son Hira Singh,

upon all of whom he conferred the title of Raja with princely fiefs for their

maintenance.

The three Dogra brothers, poor but of good family, entered the

Sikh service as troopers.

Handsome and well educated, they soon attracted (Maharaja's)attention

by their ability, determination and bravery, and rapidly rose to high positions,

where their influence in public affairs became paramount, but not being Sikhs,

they were looked on with jealousy by the (Sikh) chiefs.

They played deeply

in the intriguing game of that time, being it on gaining power, wealth and independence.

There are perhaps no characters in Panjab History more repulsive than Rajas Gulab

Singh and Dhian Singh: their splendid its and undoubted bravery only rendered

more conspicuous their immorality, atrocious cruelty, treachery, avarice and unscrupulous

ambition.

"The eldest of the brothers Raja Gulab Singh was generally

employed on military duties, and it was he who commanded the Dogra troops in the

defence of the Citadel of Lahore (when Sher Singh entered Lahore on 14th January

1841 in a bid to Lahore Fort from Gulab Singh).

Raja Gulab Singh held the Citadel

with some two thousand and ten guns, and some twelve hundred Sikh Infantry: the

latter could not, however, be trusted, but he kept them overawed in the places

they occupied in the Fort with four loaded guns pointed at them and four hundred

Dogra Infantry in advantageous positions overlooking them.

Prince Sher Singh

advanced to take the Fort with all (available) troops in the neighbourhood of

Lahore, numbering some fifty thousand and (carrying varied) arms. They marched

during night, occupied the city, and as day dawned, entirely surrounded the Fort

with a deep line of densely wedged men brought close up to the (Fort) walls.

Sher

Singh's guns were so numerous that they formed one connected battery round the

Fort. Twelve guns were placed opposite Western Gate (of Fort) and six opposite

its Eastern Gate.

Calmly and silently the besieged viewed these formidable

preparations for the assault.

Suddenly the entire circle of guns, some two

hundred in number, opened fire of blank cartridges in expectation of terrifying

the defenders.

At length the firing ceased, and the guns opposite the (aforesaid)

two (Fort) Gates fired a crashing ilium of a bull with canister of grape placed

over the beast, which utterly destroyed the Gates, and the Sikh columns headed

by fanatical Akalis dashed forward for assault.

Gulab Singh had howitzers placed,

close to the Gates and commanding them and the inward ascent from them, four guns

heavily charged with grape, which were fired into the dense crowd of assailants,

killing great numbers and driving back the rest.

This success at both Gates,

and the promptitude with which the Dogras lining the (Fort) walls without waiting

for orders poured a rapid fire of musketry upon the confused masses below, soon

clearing the besiegers from their proximity to the (Fort) walls and Gates:

they

had to retire to a more respectable distance, deserting many of their guns.

For

five days the Sikh troops (outside the Fort) maintained heavy fire, making several

breaches, but not daring an assault.

On fifth day Raja Dhian Singh with some

Dogra troops arrived at Shahdara on the opposite side of Ravi some three miles

from the Fort.

Prince Sher Singh went to Dhian Singh and begged him to arrange

matters between him and Gulab Singh so that the latter should surrender the fort.

This was done, and the Dogras marched out with all honours of war, taking with

them their entire property as well as much treasure.

After the murder of Sher

Singh and that of Raja Dhian Singh by the Sandhanwalia Sardars, Gulab Singh became

for a time the most important person in Lahore State, and his services to the

British during the Satluj Campaign were such that he was granted the independent

sovereignty of the Province of Kashmir on the payment of a million sterling.

Gulab

Singh ruled Kashmir for many years with an iron hand

In 1857 during the crisis

of Indian Mutiny Gulab Singh aided the British Government with a strong Contingent

of his troops.

Gulab Singh died (in August 1857).

COMMENTS

In

1818 Dhian Singh replaced Jamadar Khushal Singh as Chamberlain and was created

Raja. In 1822 Gulab Singh and Hira Singh were created Rajas. In 1828 Dhian Singh

received the title of Raja-i-Rajgan and was raised as Prime Minister.

According

to a manuscript in Hindustani preserved in the British Library in London vide

Accession Number Or. 1733 Raja Dhian Singh, Raja Gulab Singh, Raja Suchet Singh

and Raja Hira Singh were, respectively, granted Jammu, Akhnur, Ram Nagar and Jasrota

as fiefs.

Dhian Singh and Gulab Singh entered Ranjit Singh's service as troopers

in 1811. Two years later they summoned Suchet Singh for joining them at Lahore.

In

enumerating the virtues and vices of Gulab Singh, Sir John W. McQueen literally

repeats the version preserved in H. Lepel Griffin's work Ranjit Singh except that

he adds the word immorality in the list.

Griffin and McQueen do not lie when

they describe Gulab Singh as avaricious. In July 1840 Maharaja Kharak Singh rebuked

Gulab Singh for his removal to Jammu the property and money from Minawar Fort

and other forts in Minawar region.

We may present as an instance of Gulab Singh's

military prowess his valorous participation in the siege of Multan in 1818, which

elicited applause of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Governor-General Lord Dalhousie's

letter dated 18th February 1849 to Sir Henry Lawrence referred to in Bhai Kahan

Singh Nabha's Panjabi work Mahan Kosh contains following comment on Gulab Singh's

conduct:

... regarding Goolab Singh, you disclaim

being his admirer, and urge your desire to make the best of a crooked character,

I give you the fullest credit for both assurances.

In

his work Life of Lord John Lawrence, R. Bosworth Smith refers to Gulab Singh as

an unscrupulous villain (who secured Kashmir by paying to the British Indian Government)

down at once in the hard cash) which he had stolen from the Lahore Durbar.

Gulab Singh actually ruled Kashmir for less than eleven years. Under unofficial

secret instructions of the Prime Minister of Lahore Misar Lal Singh, the Governor

of Kashmir Imad-ud-Din delayed delivery of possession of Kashmir to Gulab Singh

who sough British help to coerce Imad-ud-Din to quit Kashmir valley. At long last

on 23rd October 1846 Imad-ud-Din moved out of the capital of Kashmir. Gulab Singh

entered the capital of valley as de facto ruler of Kashmir on the 9th November

1846 at the hour recommended by the astrologers as auspicious. Kashmir had been

transferred to Gulab Singh by provisions of the Treaty concluded at Amritsar on

the 16th March 1846. A gap of eight months spanned between Gulab Singh's de jure

title to Kashmir and its de facto control by him.

Gulab Singh undertook to

send two thousand soldiers as aid to his erstwhile British benefactors, but before

they departed, death gripped him. His successor fulfilled the promise earlier

made by Gulab Singh.

RAJA DHIAN SINGH

Raja

Dhian Singh, the second brother, was, during Ranjit Singh's life and until he

was murdered in 1843, the most conspicuous and powerful of the three Dogra brothers,

and was virtually Prime Minister for some time.

When the deposed Maharaja Kharak

Singh died, not without suspicion of poisoning, and his son Nau Nihal Singh met

his death by what was called an accident, the designing Prime Minister supported

the Queen Mother Chand Kaur in her claim to govern on the ground that her deceased

son's widow was enceinte. Also at the same time he inspired Prince Sher Singh

to advance his claim to the throne, as a son acknowledged by Ranjit Singh.

An

armed contest commenced between the two claimants.

The Prince appealed to the

army, secured its aid by lavish promises, and made a dash at the Capital, when

Queen Mother with a Dogra force under Raja Gulab Singh retired into Lahore Citadel

and stoutly defended it for five days, during which time some thousands were killed

and the City of Lahore plundered.

The clever Dogras, while apparently taking

opposite sides, but actually (and secretly) working in unison, actively participated

on both sides and secured much wealth.

Maharaja Sher Singh confirmed Dhian

Singh in his appointment of Prime Minister.

Though Sher Singh never trusted

Dhian Singh but fear could not govern the Panjab without Dhian Singh's help and

guidance.

On the day when Sher Singh and Dhian Singh were assassinated by the

Sindhanwalia Sardars Ajit Singh and Lehna Singh and their followers, Dhian Singh's

son Raja Hira Singh appealed to the Sikh army to avenge their deaths: this was

carried out at once by attacking and exterminating the Sandhanwalias in Lahore

Fort.

The young Raja Hira Singh brought the head of his father's murderer

to the widow, a noble Rajputni dame, who was waiting by her husband's body. Placing

his father's warrior plume on the son's turban, she said: "My mind is now

at perfect peace. Let the funeral be prepared, and I will follow my Lord in his

journey to the next world. When I see your father, I will tell him that you acted

as a brave and dutiful son".1

COMMENTS

Dhian

Singh held position of Prime Minister for fifteen years from 1828 to his death

in 1843.

Sir John

W. McQueen rightly dubs Dhian Singh as the Prime Minister. When Dhian Singh received

from Jamraud Hari Singh Nalwa's message asking for reinforcement for fighting

to a finish the engagement with the Afghans, he did not immediately confide the

matter to Ranjit Singh. Nalwa fell dead on 30th April 1837. Timely despatch of

reinforcement to Jamraud would have perhaps forestalled death of Nalwa. But Dhian

Singh was jealous of Nalwa and wanted quick terminus to the life of that brave

General. Dhian Singh's role in the matter elicited utmost wrath of Maharaja Ranjit

Singh.

We learn from the Hindustani manuscript preserved in the British Library

in London vide Accession Number Or. 1733 that Dhian Singh seized gold and silver

from Lama Guru and drove him to China. The same document further reveals that

Dhian Singh snatched silver from the domes and terraces of Thakurdwaras.

We

further learn from the aforesaid document that the Minawar Fort near Jammu contained

a big treasure. Whenever Maharaja Ranjit Singh encamped near Jammu, he expressed

a desire to

see Minawar Fort. Dhian Singh apparently appreciated the idea but

later he would find some excuse to take the Maharaja elsewhere.

Comparisons

are odious! While Maharaja Ranjit Singh enriched

holy

places, his Vizier Dhian Singh looted them.

RAJA SUCHET SINGH

Suchet

Singh, the third brother of the Jammu Dogra family, was the handsomest man in

the Sikh army and a splendid figure at Court, where he was remarkable for his

debaucheries.

Suchet Singh had been a special favourite of Ranjit Singh and

had free access to the royal zenana, and fully availed himself of the opportunities

to carry on intrigues with some of its fair inmates, more (particularly), it is

said, latterly with Maharani Jindan.

Suchet Singh had little of ability of

his brothers Gulab Singh and Dhian Singh, and played altogether quite a subordinate

part in lahore politics.

He was an exceedingly brave and dashy soldier and

a sabreur noted for his horsemanship and skill at arms.

(Following Dhian Singh's

murder on 15th September 1843,) Suchet Singh's nephew Raja Hira Singh was (raised

as) Prime Minister to Maharani Jindan who thenceforward acted as Queen Mother

and Co-) Regent (with her brother Jawahar Singh) for her son Dalip Singh.

Suchet

Singh was a lover of Maharani Jindan, who on her part turned his affection and

bade him aspire to Wazarat (or Viziership) which she promised to bestow on him

should he succeed in having Prime Minister Hira Singh deposed. Jindan (on her

part) disliked Hira Singh on account of his strong control in State matters.

When

Sher Singh and Dhian Singh were murdered (on 15th September 1843), Raja Gulab

Singh was not at Lahore. He went there some months afterwards in order to carry

with him to Jammu a large quantity of money, jewels and other property he had

at Lahore and also to consult and to come to an understanding with his nephew

Raja Hira Singh as to how State and other matters were to be managed by them to

their mutual advantage.

Raja Gulab Singh persuaded his brother Suchet Singh,

over whom he had great influence, to return with him (from Lahore) to Jammu, and

after a time further persuaded him that as he had no son, he should adopt a son

of his as heir to his Estate and wealth. Suchet Singh adopted Gulab Singh's third

son as his heir.

Shortly after this the Sikh troops at Lahore demanded an increase

of pay etceteras and on the Prime Minister's rejecting their demands surrounded

his house with clamorous mobs and on the third day threatened him with deposition

or death, unless he complied.

In the meanwhile news of this and also a request

from Sikh Regiments to Suchet Singh to come to them quickly reached Jammu. This

(solicitation) he hastened to avail himself of, as he perceived (therein) an opportunity

it would give him to win over with lavish promises all Sikh troops, and with their

aid to depose Hira Singh.

Suchet Singh therefore without delay started for

Lahore with such troops as he had with him at Jammu.

He arrived at a ferry

on the Ravi seven miles from Lahore on the evening of the day when Hira Singh

had won over the Sikh troops by giving in to their demands.

Leaving the main

portion of his troops on the north bank, Suchet Singh crossed over to the south

bank with some three hundred and fifty men, and occupied (an old Mosque) and ground

near it not far from the ferry.

Suchet Singh had hardly done so, when messengers

from the four Regiments, which had invited him to come to Lahore arrived and told

him what had happened, and advised him to return at once to Jammu, as it was now

impossible for them to help him in any way.

He later heard from his nephew,

the Prime Minister, that he was marching upon him with the Khalsa army and threatened

him with destruction, unless he went back at once to Jammu.

But the Dogra,

rash as he was brave, remained on quietly in the old Mosque where he was resting,

but his party of about three hundred and fifty men, who had crossed the river

with him, rapidly dwindled to forty-six before morning, when they were surrounded

by some ten thousand Sikh troops under Hira Singh with fifty-six pieces of Artillery,

which opened fire on the Mosque and after a little time all of the Sikh troops

advanced en masse to (launch) attack.

When they had approached to within a

hundred yards (from Mosque), Suchet Singh and his handful of heroes, swords in

hands, rushed upon a thick mass of their enemies, and so fierce and desperate

was their assault, that they actually broke through and drove back a great number.

But

their desperate valour availed not the devoted band so fearfully overmatched!

Raja

Suchet Singh and forty-two of the brave band were lying dead on the field: four

fell badly wounded, of whom only one survived.

Thus fell the gallant Suchet

Singh and his staunch band of Dogras, performing prodigies of valour: the names

and deeds of some are still famous in the Sikh Story as well as Dogra Story.

The

total loss of the attacking Khalsa force is said to be about one hundred and sixty

killed and wounded.

When the handsome Raja Suchet Singh was killed at Lahore,

his ten wives and some three hundred unmarried ladies of his zenana committed

Sati, some at Lahore, some at Ram Nagar where his head was brought and others

at Jammu or at their homes.

COMMENTS

Gulab

Singh reached Lahore on 10th November 1843. Hira Singh hated his uncle Suchet

Singh because the latter had soft corner for the holy man Baba Bir Singh of Naurangabad

who had a quite enormous following among Sikhs. Suchet Singh respected Baba Bir

Singh while Hira Singh discerned in the latter a potential danger to his pelf.

Gulab Singh utilised his visit to Lahore for rapprochement between Hira Singh

and Suchet Singh for ensuring Dogra Group's unity, which was being eroded constantly

by the sinister advice to Hira Singh by his wily and crooked Mashir-i-khas, or

Special Counsellor named Jalla. Having failed to retract the uncle and nephew

from their pernicious course, Gulab Singh chose the other alternative of keeping

the two recalcitrants at a distance. He advised Suchet Singh to accompany him

to Jammu. On 4th December 1843 Gulab Singh and Suchet Singh left Lahore for Jammu.

On

arrival at Jammu, Gulab Singh prevailed upon Suchet Singh to adopt the former's

son Ranbir Singh. Suchet Singh did the needful.

Among the wounded persons who

gasped on the battlefield lay Suchet Singh's Counsellor Rai Kesari Singh who asked

for water. A sardonic smile played on the latter's lips when Hira Singh told him

that rather than marching down to plain he should have preferred stay in the mountains

where there is no dearth of cold potable water. Perhaps a drop of water would

have lengthened Rai Kesari Singh's lease of life. However, the practice of denying

water to one's son going to battle against odds, and pouring water into the mouths

of the foes wounded on the field, dating back to the days of Guru Gobind Singh,

elicited no appreciation from the hard vetch named Hira Singh. Rai Kesari Singh

had already slain twenty enemies when he sustained serious wound and fell aground.

The battle took place on 27th March 1844

RAJA CHATAR SINGH ATARIWALA

Sardar

Chatar Singh was the head of the younger branch of the Atari family, who (towered

over) Sidhu Jats, the best blood of the Majha. He took no share in politics during

the reign of Ranjit Singh, but his family possessed great influence at Court,

and in 1843 his daughter Tej Kaur was betrothed to Maharaja Dalip Singh.

In

1846 he was appointed to succeed his son Sardar Sher Singh as Governor of Peshawar,

but his rule was no purer than that of his son. The corrupt politics, that both

indulged in, astonished even the Lahore officials, but the family was too powerful

to be lightly offended, and too nearly connected with Maharaja (Dalip Singh) to

be passed over.

Chatar Singh was transferred from Peshawar to the Governorship

(of the region) between the Indus and Jehlam Rivers and Sher Singh was received

in the Lahore State Council and a little later got the title of Raja. This honour

had been recommended for bestowal on Sardar Chatar Singh, but at the last moment

he requested that instead his son be given it, and his wish was granted.

When

Multan Outbreak occurred in April 1848, Chatar Singh Was in Hazara. His troops

were notoriously disaffected towards lahore Government: this disaffection he shared

and encouraged. At first Chatar Singh had only two thousand men, but he rapidly

increased their number, and sent them to his son Sher Singh for his aid and also

to Maharaja Gulab Singh of Jammu, and encouraging him in his actions, also to

Amir Dost Muhammad Khan.

Chatar Singh raised levies in Peshawar and in his

own districts, and used all means in his power to make his rebellion as formidable

as possible. After taking Attock Fort on 2nd January 1849, Chatar Singh marched

from Hazara with a considerable force to join his son's army, which he did (on

16th January 1849) three days after the Battle of Chillianwala.

On 21st February

1849 was fought the decisive, and for the British the brilliant and memorable

Battle of Gujrat with the united Sikh and Afghan army of some sixty thousand men,

which was completely defeated by Lord Gough with the heavy loss of men and fifty-three

guns. This was virtually the end of Panjab Campaign. The victory was followed

up with vigour, and at Rawalpindi, on the 14th March 1849, Chatar Singh and Sher

Singh with what remained of Sikh army, some sixteen thousand men, laid down their

arms.

After this, Sardar Chatar Singh and Raja Sher Singh were sent as prisoners,

first to Allahabad (Fort) and then to Calcutta. Their Estates were confiscated,

but they were granted fitting allowances.

In January 1854, they were released

from confinement and allowed to choose their places of residence within certain

limits. Also their allowances were considerably increased. Chatar Singh chose

to remain in Calcutta where he died early in 1858.

COMMENTS

The plain territory between Rivers Bias and Ravi is known as Majha.

The British

authorities did not let the betrothal mature into marriage. At long last Tej Kaur

was got married to Janmeja Singh Gill of Mariwala. She gave birth to two sons.

In Allahabad Fort, Chatar Singh and Sher Singh were not permitted to sleep

outside their cells. They perspired while they slumbered during nights

Actually

Chatar Singh died in Calcutta on 18th January 1856.

RAJA SHER SINGH ATARIWALA

He

was an able and spirited man who ruled that difficult district to the satisfaction

of Lahore Government.

Sher Singh Atariwala was Sardar Chatar Singh Atariwala's

eldest son.

In 1844 Sardar Sher Singh was appointed Governor of Peshawar.

He

was an able and spirited man who ruled that difficult district to the satisfaction

of Lahore Government.

Sher Singh Atariwala successfully put down a Yusafzai

insurrection, but his administration though vigorous was usually corrupt. He was

moved to Lahore and made a Member of the State Council and shortly afterwards

given the title of Raja.

In April 1848 occurred the Multan Outbreak and Diwan

Mul Raj stood forth as a rebel against the Lahore Government. Sher Singh was sent

to Multan with a Sikh force, which joined Lt. (Herbert) Edwardes near Multan Fort

on 6th July. Although the Sikh army was disposed to mutiny, Sher Singh had sufficient

influence over it to keep it tolerably under control, and on 20th July (1848)

it co-operated with Edwardes' force with energy and success.

On 18th August

(1848), General Whish, with a British force, reached the neighbourhood of Multan

and was joined by the troops under Edwardes and Sher Singh Atariwala.

On the

following day news was received of the rebellion of Sardar Chatar Singh and his

army in Hazara. Although Sher Singh constantly received letters from his father

to join him, he and some of his Sardars did their utmost to suppress the spirit

of mutiny among their men, and even got them to take part in the operations before

fall of Multan.

However, on 14th September (1848), Sher Singh's whole camp

rose in mutiny. His and his Sardars' lives were threatened, and at last in desperation,

he went over to the side of rebels and marched with his force to Multan, when

he had to camp outside the walls of the Fort and City. Mul Raj distrusted him,

and refused him admittance into either.

This defection of Sher Singh's large

force compelled General Whish to raise the siege of Multan for a time, until reinforcements

in men and siege guns should reach him.

Finding Mul Raj distrusting him, Sher

Singh decided enjoining his father at Hazara. Mul Raj, to hasten his departure,

advanced him a considerable sum of money, and Sher Singh with some five thousand

men marched from Multan.

On 22nd November (1848), Sher Singh's force received

a check at Ramnagar from the British army under Lord Gough.

On 3rd December

(1848), Sir Joseph Thackwell attacked Sher Singh's position at Sadullapur. The

action was indecisive, but on the night of 3rd December Sher Singh retreated towards

the Jehlam, and took up a position at Chillianwala, where on the 13th January

1849 the British army under Lord Gough attacked him. The account of this battle,

little creditable to the British, has often been written. It has been called a

victory (by Sikhs), but neither the (British) Generals nor their soldiery ever

considered they had been defeated. Both sides fought well, but the hero of the

day was Jawahar Singh, the son of the famous Sikh General Hari Singh Nalwa, who

led the Sikh cavalry charge that had so great influence on the result of the battle.

Six

weeks later on 21st February 1949 Sher Singh aided by hiS father's and Dost Muhammad's

forces fought the Battle of Gujrat. His army was decisively routed with heavy

losses in men, guns and material. This was their last battle of the war, for a

few days later the whole Sikh army gave up their arms at Rawalpindi and dispersed

to their homes.

After that Sher Singh was placed under surveillance at his

home but being discovered plotting treason was sent a prisoner (to Allahabad Fort

and later) to Calcutta. His property was confiscated, but he was granted an allowance.

In

January 1854, Sher Singh's conduct having been irreproachable since the annexation

of the Panjab, he was released.

Sher Singh volunteered his services in Burmese,

Persian and Southall campaigns, but they were not accepted.

At the outbreak

of the great Indian Mutiny, Sher Singh Atariwala supported the British authorities

as far as it lay in his power and sheltered in his house several British residents

of the place.

Raja Sher Singh Atariwala died in exile in 1858 far from his

own country at the sacred city of Banaras by waters of the Holy Ganges.

COMMENTS

Chatar

Singh had five sons and one daughter.